México

Why are journalists killed in Mexico?

By Paula Mónaco Felipe

It’s been said that journalists are targeted by drug cartels and government officials, shielded by impunity. There is no single explanation for the rise of violence over the past 20 years. It is the reason we chose to analyze this worst period: Veracruz 2010-2016. In a state with at least seventeen journalists killed and an additional three disappeared, we find out that fear persists, the information disappears, many are cold investigations, the killers are at large, and many now hold greater authority. A third decisive actor was also identified: the media corporations. The private sector is a concentrated, harmful mix of conflict of interests and inequality. Now, several new clues shed light on the who, what, how, and why journalists are killed.

1. Page editing

It’s afternoon rush hour. Running to ensure the article is well-written, checking if the photos are there. Adjusting here, cutting there. The headline: Is it good as it is, or should it be changed? There’s no quiet newspaper in the afternoon; everything is against the clock.

The windows are open at Dario Cardel because it’s hot; here, the temperature reaches up to 30 degrees even in winter. Worse still, if the north wind blows, a soporific wind that gives headaches and invades every corner.

«What’s to be published tomorrow?» asks a man through the window.

He asks today as he asked yesterday, and he will ask tomorrow. And it won’t be just one man, but many. Sometimes with visible weapons, the boss’s people. Other times without showing guns because it’s not necessary; everyone knows who they are. They often come to the newspaper, asking what will be in the next day’s edition.

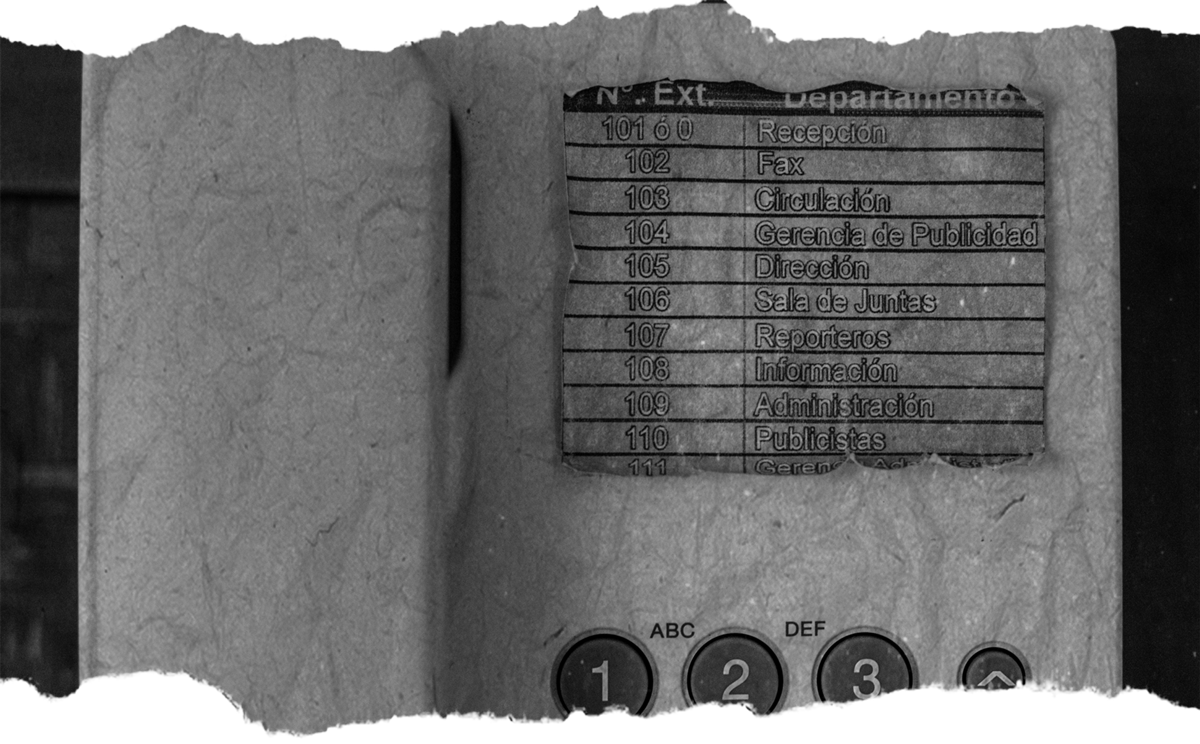

They’re not the only ones; some afternoons, the police also knock on the door. They come from various departments to check and decide what news will make the headline, what photo is in it, or how it’s framed. Furthermore, they knock, ask to come in or wait outside for detailed information. In other Veracruz cities, actually, in many cities, the press is controlled by phone. Calls at night to let reporters know what could be published; messages to reporters’ phones to dictate what will be news

It’s known that for years, some major newspapers in Veracruz have sent their front pages for review by the sitting governors; however, in Cardel in 2012, the limit is beyond anything imaginable. Drug cartels and police come to check—and sometimes – edit the front page.

José Cardel is a city with 19 thousand inhabitants and much more importance than this number might suggest. Here, the federal highway 180 crosses the country and converges with the state highway number 40, which connects the port with the state’s capital, Xalapa. Additionally, the train passes through here. And it’s only 30 kilometers from the economic capital, Veracruz-Boca del Río.

José Cardel is highly valuable as a trading location, whether legal or not. That’s perhaps why it has been held hostage to the disputes between cartels. With the arrival of Matazetas in Veracruz, it was one of the first places to conquer to wrest territorial control from Los Zetas. In the same place, where there used to be a popular carnival and green fields of sugarcane, death began rotting everything. Murders first, bodies thrown afterward. Decapitated, mutilated remains were placed in garbage bags and disappeared; the days became difficult and the nights impossible.

From 2007 onwards, it was a very dark time here. Organized crime entered and took over many media outlets, as well as many who worked for it. It wasn’t possible to even chat—even if you were at home—because the criminals found out what you were talking about, recalls someone who used to live in Cardel and decided to flee to feel safe.

No one wanted to talk, but everyone wanted to read. The business of crime reporting exploded. Diario Cardel came to sell between three thousand and three thousand five hundred copies every day, meaning one out of every six residents bought the newspaper.

Every morning, on motorcycles with loudspeakers like those in advertising cars, the most important news was announced through the streets. And people rushed to buy. Blood sold.

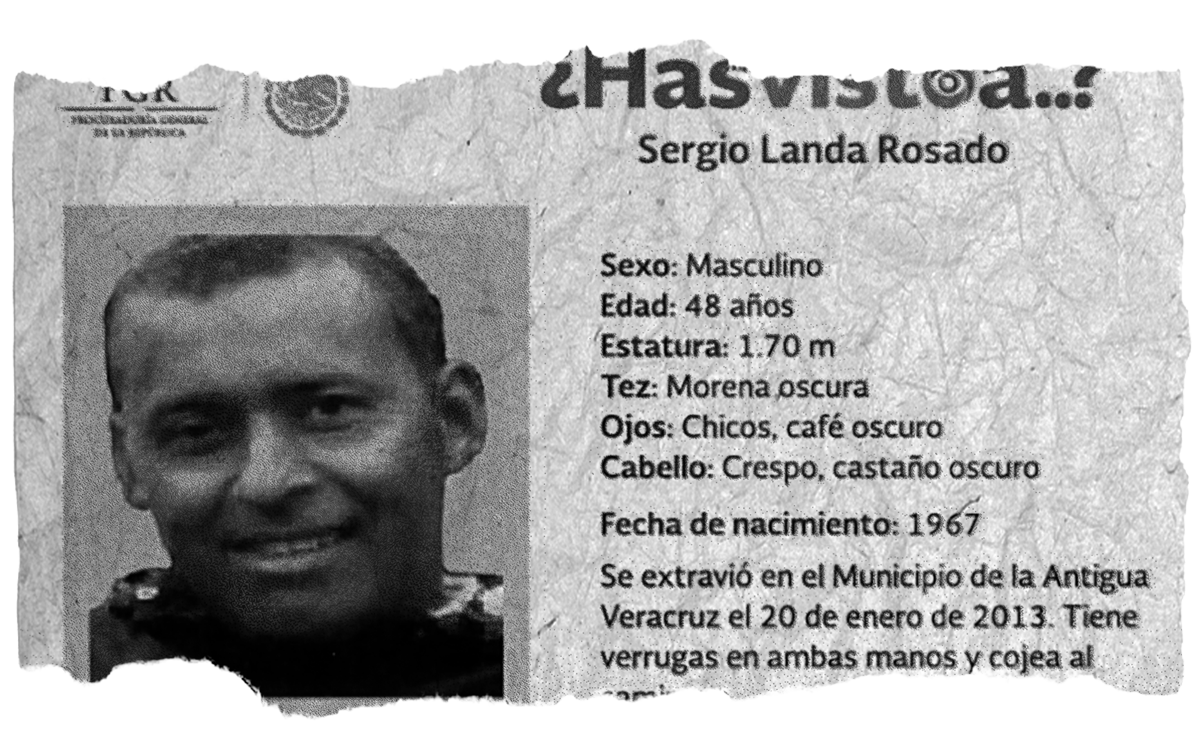

In the photo, he smiles, showing his candidate registration as a congressman. He wears a white polo shirt and carries a backpack on his left shoulder.

«Foul-mouthed like the entire Veracruz fleet. But noble, honest, and without malice,» describes his former colleague, Jesús Augusto Olivares Utrera, to Sergio Landa.

He says Landa was always popular and beloved in his community, which is why Nueva Alianza offered him a registration as a candidate for congressman for District 13th of Huatusco. He never took the position; he withdrew one day before the elections because the political party had not fulfilled the promise to finance the campaign with a car and a media agreement with the outlet he worked with. Sergio Landa was born in El Zapotito, a town that today has 762 inhabitants and was even smaller during his childhood. His parents were farmers, and he had many siblings

He liked to draw and always hoped to study. He started a career in graphic design but could not finish it due to a lack of money to pay for his studies. So he became a sign painter, an old trade that consisted of hand-painting letters, logos, and advertisements on signs or walls.

Sergio also made belts and was a soccer referee. His friends remember him as a partygoer, dancer, and salsa enthusiast. But also an entrepreneur, some one tha had a big heart and was fearless with a desire to thrive to go head. Perhaps that’s why he became a journalist.

He was unemployed when he learned that Diario Cardel was hiring a designer. Upon arrival, it turned out they needed a reporter, and Sergio said yes, even though he had never worked in the media before. His was remered for his enthusiastic but haphazard approach, some called him Speedy González because, he raced at full speed on his motocycle to arrive on time at the crime scene. Others called him the rubber journalist because he often fell from the bike but quickly stood up.

As he contacts expanded over the months: Landa made connections in the armed forces, emergency services, police departments, and, like almost everyone, always including people in uniform. He talked to them, tried to negotiate the stories, and in front of him, they called the «papás (fahers),» as they referred to the police, to ask questions, request clarifications, and turned orders.

Sergio became a reporter by trade, as they call those in Veracruz who didn’t study journalism but became journalists by trade through hard work. Once inside, he liked the adrenaline rush, but above all, he was drawn to the crime news; as they say, it gets under your skin. If you like covering crime stories, it’s a job you can’t escape—a kind of addiction.

In those years, journalism in Veracruz was exciting but not an easy livelihood. Because violence was increasing, this became a big business.

Media entrepreneurs pushed for the most explicit photos and revealing information; that sold. Similarly, the cartels forced their agenda: Los Zetas wanted to show their executions to instill terror, and Los Matazetas (later Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación) ordered not to show any blood because they wanted to have a different image, while journalists,were caught in the middle.

Pressure was coming from every directions, and orders often contradicted each other. To whom should we listen? How do you refuse when the threat is an implicit order?

To make matters worse, reporting in Veracruz during those years meant risking one’s life for not much money. At first, Sergio Landa started earning 1,500 pesos every two weeks, or 107 pesos per day. After a couple of years, he was able to earn up to 2,500 pesos every other week, without social security or paid time off. Less than ten dollars a day.

He was kidnapped twice, in 2012 and 2013, but did not return the second time.

2. The agreements

A mystery: at least 27 media outlets, almost all newspapers, closed in Veracruz around the year 2016.

Some of them are: El Diario del Sur, AZ Veracruz, Milenio El Portal, Marcha, Oye Veracruz, and Capital Veracruz. Also, El Diario de Minatitlán, Matutino Expréss, El Mundo de Poza Rica, El Despertar de Veracruz, Veracruz News, La Voz del Sureste, and Mundo de Xalapa, among others. They are from different regions of Veracruz; they all have different histories and owners; however, they all stopped publishing almost at the same time, disappearing from one day to the next as if stricken by an evil spell. The mystery deepens: around the same dates, at least five other newspapers canceled their print editions and migrated purely to digital. Many closed or reduced newsrooms to a minimum.

The crisis facing print media is global; even The New York Times has considered ceasing printing, and other major outlets like El País have canceled editions in some regions. But something else happened in Veracruz at the end of the 2010–2016 government administration. The malaise that spread from newsroom to newsroom was the end of the magical potion that sustained everything: agreements.

By agreements, we mean direct allocation of contracts by the government of Javier Duarte which authorize news companies to publsih contect commonly known as official propaganda. These funds were sometimes untagged, with unclear objectives, and handed out as blank checks.

State announcements are necessary because media companies are businesses that need financing, however in Veracruz and many other states, they have been used as rewards for compliance and incentives for tailored coverage.

The official agreement or the allocation of state resources to the media is not new; decades ago, former president José López Portillo made it clear: «I don’t pay to be criticized.» Nor is the weight of state advertising new; such vital funding exists nationwide that it represents nearly 60% of media income, according to independent studies. In Veracruz, Fidel Herrera’s government is remembered for handing out money as he went, but during Duarte’s administration, this situation reached exceptional dimensions. ‘Behave well,’ Governor Duarte would tell journalists, while a specific branch of his government handled his intended message.

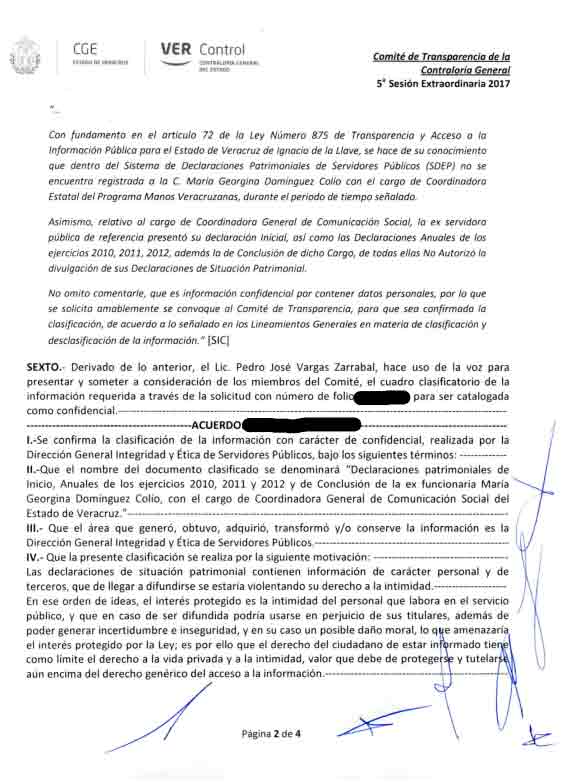

The Office of Social Communication went from having a budget of 50 million pesos in 2011 to 304 million pesos in 2016. It multiplied by 452 percent, according to the 2011 Budget Law and a report prepared by the Superior Audit Office at the request of local deputies. Later, outrageously higher figures were disclosed: Duarte’s government paid nearly 5 billion pesos in press agreements, or about 294 million dollars, according to statements by Prosecutor Julio Rodríguez Hernández in a pretrial hearing.

The destination of that budget was decided by just one person: María Gina Domínguez Colio. With short hair, blonde highlights, thin eyebrows, and a fierce look, she was one of the strongest figures in the administration. As a result, she was nicknamed the Vice Governor. In addition to her personality, her professional background stands out: she is a journalist with extensive experience, familiar with every aspect of Veracruz’s media landscape.

– She was in charge of damage control, says a journalist who requested anonymity. She denied the news. She called newsrooms and ordered, “Take down that story; put this one up.” She identified people and put them in danger. She was so powerful that when they found the 34 bodies in houses in a residential area of Boca del Río [in 2011], Gina denied the news, and then the Navy denied her. Yet, she was not dismissed.

Mountains of money were in Domínguez’s hands, perhaps even more amounts than what the documents disclosed because, at the end of the administration, there were pending agreements to be paid. The debt, with details of companies amounted to at least 400,146,820.86 pesos when the authorized budget for that year was theoretically 304 million, according to Plumas Libres. Although journalists requested the amounts and details of payout to media, the government responded that it was classified information.

Prices of silence. “The debts owed to the media outlets and journalists who helped to throw ‘incense’ in the path of the current governor, to hide shootings and deaths, and to report violent events as robberies, when in reality, in some cases, they were executions. Making people to look the other way when they knew the case was about a mother looking for her son, disappeared by the Zetas, by the Jaliscos, or by police patrols,» says a text by Ignacio Carvajal published on July 11, 2016. Years later, in 2023, during the presentation of a book in Mexic City, journalist Norma Trujillo summarizes: «In Veracruz, there are no exactly independent media outlets; advertising sets the tone.»

Another colleague who asks not to reveal his name says it almost without surprise, as something normal:

It is well known that almost all media outlets reported on Duarte’s social communication. It was my job when I worked at the newspaper I mentioned; I was in communication with [a particular person] because I was the editor-in-chief and was asked to contact him to know what statement the governor wanted to release. I always called him. That’s how it went for years.

Another journalist, also speaking on condition of anonymity for security reasons, continues:

Gina would have fired reporters if they went off-script. She supervised the photos and what should or should not be out in all media outlets. The intimidation was fierce. First, the obvious: censorship. If you kept insisting, she scolded you or got you fired; they would suspend or delay your [agreement’s] payments. Those were systems, perfectly designed. And if, despite being fired from all media outlets, for example, let’s not exaggerate the point, if you retained some [jobs], she continued intimidating you, they pursue you, they monitor you, and the last one is they give you ‘beatings’. No, sorry, the last one is death. Because that was something we witnessed perfectly, they started doing it a lot. But I don’t know exactly how she operated; it was all rumors.

The increasing power of agreements during the Duarte era, created surreal situations unleashed. In 2015, when some journalists protested to demand the outstanding payments for official propaganda, two executive directors stood in front of the government palace in Xalapa with signs saying, «There are no longer money envelops handed out; the government has other priorities.».

According to documents published by Noé Zavaleta in Proceso, the Duarte administration annually paid «between 200 and 230 million pesos in pro government publicity on radio, press, and television (…) And although that money was labeled, it was not always paid.»

The scandals accumulated; it became imminent that Duarte’s runaway, along with part of his cabinet, would continue; nevertheless, the debts remained. For example, the newspaper Marcha was among those that suddenly disappeared and to which the government owed 4,788,000 pesos. AZ also vanished, and it had an outstanding balance of 27 million pesos.

According to a list disclosed in 2016, there are 127 unpaid agreements . It includes legal entities, anonymous variable capital companies, and the names and surnames of individuals. There are publishing houses, communication companies, radio companies, and consultancies mixed with acronyms that say little. Most of them are linked to the state of Veracruz, moreover there are leading national media such as El Universal ($3,800,000), Excélsior Newspaper ($4,000,000), the NRM Communications Group ($2,970,400.31), and the Reporte Índigo ($7,795,200).

This is a list of those that tried to claim debts at the end of the 2010–2016 administration, with no certainty about the total number of claims or the destination of the money that came out of the Veracruz communication office during that six-year term, or the office of Gina Domínguez. In 2023, more than a decade later, the Contracts and Agreements office of the Veracruz government responded via transparency that «the requested information is not available.» Either they have nothing to share or they share nothing.

3. Is it possible to say «no»?

It was one of those routine stories—the ones that don’t matter much. Taxi drivers protested to demand greater security. A brief article that appeared in the print edition which seemed to get lost among the others. However, at eleven in the morning, the editor called.

«Are you okay? There was a problem with the story you published.»

«But it’s informative!»

«You know you’re not supposed to publish those things.»

His stomach was tied in knots, his heart raced, and a shiver went down his spine. Journalists in Veracruz know how much danger lurks behind the phrase «there was a problem with your story»: it means life is in jeopardy.

The phone rang again. It was the cartel calling him to a location. One of those calls that can’t be ignored and one of those appointments you’re obligated to attend even though you know you might not come back.

He went to the designated spot. They drove by in a medium-sized white car and ordered him to get in. Inside were young men with shaved heads and many tattoos. Clearly visible was a large AR-15 rifle.

«We cover what happens. Our editors-in-chief decide what to publish and what not to publish,» he tried to explain, to excuse himself.

«…Your boss already knows what goes and what doesn’t. Don’t you know we pay your boss? Doesn’t he give you anything?» responded the zone chief with a certain degree of astonishment. «Here’s my number. Next time, you call me.»

The terror of non-negotiable calls and appointments. The certainty that the zone chief paid the director and by him acceptiing the resources, more certained conditioned the editoral …..process Much less, he distributed that money.

Payments at the newspaper were forty pesos, or two dollars per story.

Two dollars every time one risks their life because in Poza Rica, where the story unfolds, the years 2010–2016 were hell. The journalist narrating asks to omit any detail that could reveal his or her identity, as the same people still in power and the risk still persists a decade later.

«If something happened to you before and you went to the police, they handed you over to “them”. You couldn’t even go out at night or stand in dark places. It was terrible. There were thousands of crimes here that weren’t publicized. They weren’t in the press or anywhere else because they didn’t want them to be exhibited (…)

When they removed the police, everything got worse (…) Now there are the four [cartels]: Los Zetas, who call themselves Grupo Sombra, the Sinaloa Cartel, Jalisco [New Generation], and Old School Zetas. In the main square of Poza Rica, the murals from the oil boom era or the great work of Pablo O’Higgings, which portrays the golden years, are barely seen anymore. More and more banners of missing persons are being hung in the gazebo, from tree to tree, and on the pedestrian bridges.

At the other end of the state, in the southern region, is the basin of the Papaloapan River. In Tierra Blanca, one of its most important cities, they said the idea of free journalism has been completely erased.

– They forced you to write what they wanted and what they didn’t. They’d say, ‘this yes, and this no.’ Or you’d arrive to cover [the crime scene], running into them, and they’d just gesture a ‘no’ with their finger. We wouldn’t even take out our equipment anymore. They didn’t give us or offer money here. They call us accomplices, but it’s not like that. In Tierra Blanca, was a ghost town for awhile. We lived with our necks on the line, recalls another journalist who also requested anonymity for security reasons. He continues working and says that Tierra Blanca sometimes is still a ghost town. Before, it was due to kidnappings; now it’s due to extortion, executions, and shootings.

Similar accounts are repeated in various regions of the state of Veracruz, a territory so vast that it could well be a country: 71,820 square kilometers. Lands ravaged by violence and fear, places where the police were (and sometimes still are) involved in crime. So much so that former governor Javier Duarte chose to dissolve the inter-municipal police forces: in Xalapa, in May 2011; in Veracruz-Boca del Río, in December; in Coatzacoalcos-Minatitlán, in May 2013; and two months later, the one in Poza Rica-Tihuatlán-Coatzintla.

Duarte dissolved all the intermunicipal police forces. The Navy took control of security, and armed forces were deployed throughout the state. On April 10th, 2011, alongside former President Felipe Calderón, Duarte launched the «Veracruz Secure» operative, which paved the way for a federal single command with military troops, increased security resources, and the cleansing of police forces. At least in theory, because the strongman of Duarte’s security, Arturo Bermúdez Zurita, had other plans. “Captain Storm,» as he was called, a former Secretary of Public Security and responsible for the State Police, decided to launch his own special forces.

In 2012, Bermúdez diployed an elite unit called Grupo Tajín, named after the most importan pyramid in the area. At an event that Duarte did not attend, Bermúdez Zurita said that 206 police officers were trained for four months by the Navy. He added that the goal was to provide «the first contact, rescue, and act with the civilian population,» but the project barely lasted and hardly fulfilled these goals. Grupo Tajín was a corrupt force that sank a year later when elite officers kidnapped eight police officers in the municipality of Úrsulo Galván who are still missing.

In 2014, Bermúdez Zurita tried again with a second group, the Fuerza Civil. Once again, the promise of an elite group and the bet multiplied by ten: there were already two thousand police officers. The former National Security Commissioner, Monte Alejandro Rubido, was present at the event. But security did not improve with the Fuerza Civil either, and murky events multiplied.

Even before the end of the 2010-2016 administration, journalist Noé Zavaleta published his book «El infierno de Javier Duarte» (Proceso, 2016). By that time, he said, there were already at least 470 municipal and state police officers under arrest «to be investigated for federal crimes, especially those related to drug trafficking.» His research shows that both Los Zetas and the Jalisco New Generation Cartel had «infiltrated the police forces» and even divided the territory: police officers from the mountain and southern regions worked with Los Zetas, while those from the coast and Sotavento worked with the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG).

Another writer, Juan Eduardo Mateos Flores, portrays the police metamorphosis of the port, in his book «Reguero de Cadáveres» («Trail of Corpses»). He recounts how that territory, which was completely folded into the power of Los Zetas, whom they called «La compañía» («The Company»), began to mutate into «Zetas volteados» («Turned Zetas»). With thick-rimmed glasses, flip-flops, and slang when speaking, Mateos Flores narrates the change in territory control through the stories of young people who died in the neighborhoods. He recounts the precise moment when the new cartel entered the zone: they introduced themselves as the Matazetas and by throwing 35 bodies on the streets; however, “since then, such personnel had begun to operate, unaware, for the Jalisco New Generation Cartel'».

Noé Zavaleta, the young journalist who dared to cover Veracruz for Proceso after Regina Martínez murder, underlines two names that are always present in the darkest stories of the Veracruz police at that time: Arturo Bermúdez Zurita, «the ominous Captain Tormenta,» and among his most powerful subordinate, Marcos Conde, head of the Secretary Security in the Sotavento area.

It is no secret in Veracruz that Bermudez Zurita’s police were part of and involved with organized crime in several regions. But Zavaleta, tall and smiling, with an unusual frankness in that territory where everything seems silent, publishes that at least three training camps have been detected where state police officers taught thrained to young Zetas hitmen (sicarios). In Cumbres de Maltrata and Rancho San Pedro, for example, they were taught to shoot but also «to dig clandestine graves without leaving traces, to torture and kill.»

Masters of crime.

Violence did not appeared out of no where in Veracruz with Duarte’s government. It had already been growing for several years, and many identify the beginning of the worst times in 2007, when the dominance of Los Zetas began. It was during Fidel Herrera’s period, whose nickname was Zeta 1.

The violence persisted through the Herrera and Duarte administrations; Veracruz-born writer Fernanda Melchor calls this period ‘the double six-year term’ in the prologue to Noe Zavaleta’s book “Reguero de Cadáveres”. Zavaleta describes Duarte’s era as ‘true obscurantism.’ With no words chosen lightly, he speaks of the effects of cartel disputes, the reordering of territories, and the multiple strategies the government maintained toward the press.

-Duarte was a close friend of the media owners. For example, he invited the executive director of Diario de Xalapa at least three or four times abroad. In 2013, during the tourism fair in Madrid, Duarte took 15 of them on a trip. He even invited them to the final of the Copa del Rey at the Santiago Bernabeu Stadium.

Those owners strolled around, receiving millions of pesos in agreements but paying their journalists miserable wages. Horacio Zamora never went on those trips. He was a journalist for 15 years at various media outlets in Xalapa and the Port of Veracruz, collaborating directly with some and selling content to others. He experienced a period of executions, bodies in bags, and disappearances while attempting to make a living. He worked through those years under that type of violence; however, a decade later, he realized that there were other kinds of violence besides bloodshed on the streets.

-At the moment, you don’t perceive it; you are accustomed to thinking that it is just the boss, the newspaper’s policy, or that’s how the profession of journalism is. But the truth is, they were violating so many of your rights—labor, civil, and professional. Now you see it and realize you were exploited and abused, and they did whatever they wanted. I witnessed countless cases of abuse. The infamous censorship of freedom of expression and freedom of the press begins in newsrooms with miserable salaries, with agendas working 12–15 hours. You have no medical benefits; if something happened to you, you would be on your own to solve it. You work with your own car and resources. I think I had maybe 9 or 10 jobs at once in Veracruz.

He looks at it in perspective because time has passed, but also because he’s no longer here. He left. For the second time, he went into exile in a safer country.

– I think that everyone wants to flee from Mexico, don’t they?

He looks at it in perspective because time has passed, but also because he’s no longer here. He left. For the second time, he went into exile in a safer country.

– I think that everyone wants to flee from Mexico, don’t they?

Sergio Landa wrote and took photos at Diario Cardel. He earned 2,500 pesos every other week without

medical benefits or days off.

Rubén Espinosa Becerril earned the same as a photographer in Xalapa, while Gabriel Huge earned a little more, 3,000 pesos a week, in the port area.

Gregorio Jiménez worked at the Villa Allende municipality by writing and taking photos, earning 20 pesos per article. On busy days, sometimes he earned 100 pesos per day or about 1,700 pesos per month, plus 800 pesos for gasoline when working for the Liberal del Sur, a newspaper owned by the family of magistrate Edel Humberto Álvarez Peña, accused of multimillion-dollar ghost contracts.

Similarly, in Coatzacoalcos, a qualified staff journalist earned 3,600 pesos per month at Notisur, while interns and students earned between 700 and 1,000 pesos per every other week.

The situation was similar in the port area. Journalists earned between 5,000 and 6,000 pesos per month for most companies. Only the most popular newspaper, Notiver, paid around 8,500 pesos every other week.

If converted to dollars, these numbers are distressing: salaries of $500 per month for qualified journalists; half (or less) for those without formal training, the self-taught. Full days of work for a payment of $8 to $16.

A few cents for risking one’s life.

Coins for entering an unpredictable , disjointed war.

– Sometimes it’s impossible to escape from that situation –says a journalist–. If you ask me, did you have any relationship with those people [the drug traffickers]? I can tell you that with many, you have to learn to coexist, otherwise you won’t survive.

–The Zetas paid 15 to 20 thousand pesos per month to the media collaborating with them–, says another journalist from the port.

– Up to four times what a newspaper paid. How to say «no» when the needs are greater? How to say «no» when there is no room to decide? How to say «no» if refusing could get you killed today?

They didn’t always pay, not everyone got paid. But they did demand.

-It wasn’t optional. It wasn’t optional for those dedicated to police reporting to accept or reject the authors of the criminal group (…) I had testimonies from people who, when diplomatically refusing to follow the criminal group’s line, so to speak, to go along with it as colloquially said, well, they faced consequences (…) One was deprived of liberty, tortured–, says Jorge Morales, former member of the commission for the attention to journalists.

– You needed to fall in line with them; there was no choice, a policeman told Sergio Landa, who hours later was kidnapped for the first time.

On one side, bosses who demanded a lot and paid little; on the other, armed people above law. For many, it was not possible to refuse: you either align yourself or life was over.

4. Press kit

Only three families controlled at least 24 media outlets in Veracruz, and many of the owners of news companies were also politicians holding public management positions.

Edel Álvarez Peña, linked to the Olmeca Editorial Group, owned eight media outlets during Duarte’s tenure (plus another four in Chiapas and Tabasco). He had not background in journalist. Over several decades of his political career, he served as municipal president of Coatzacoalcos, state president of the PRI, advisers to the state government coordinator, and director of the Public Property Registry, among other positions. Proposed as a magistrate by then-governor Fidel Herrera and appointed by the state congress in 2010, in December 2016, on the first day of Miguel Ángel Yunes Linares’s government, he was appointed President of the Superior Court of Justice and the State Judiciary Council. He retired recently and was accused of corruption, including forging contracts for around 350 million pesos with ghost companies linked to the international money laundering scandal known as the Panama Papers, according to the journalistic investigation by Flavia Morales.

The second media conglomerate in Veracruz with a clear conflict of interest is La Voz del Istmo and Imagen del Golfo group, which owns five newspapers belonging to the Robles-Barajas family. All of them headed by José Pablo Robles Martínez, husband of Roselia Barajas y Olea, who was a federal deputy (1997–2000) and continued his political career by becoming an ambassador in Costa Rica, appointed by the government of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador. Their daughter, Mónica Robles Barajas, has served as a state deputy twice (2013–2016 and 2018–2021), first for the Green Party and later for Morena. She was a deputy at the same time as being the legal representative of the editorial group, according to the media registry of the Secretariat of the Interior. Mónica’s husband, Iván Hillman Chapoy, is a former mayor of Coatzacoalcos, and her brother, Pablo Robles Barajas, has been a senior official at the National Water Commission since 2012. The companies owned by the Robles-Barajas family have obtained so many official advertising agreements that, in the past, former Governor Fidel Herrera criticized Pablo Robles Martínez by calling him a «professional vacuum cleaner.»

Third but not least is Grupo Editorial Sánchez, owned by the Sánchez Macías family. They have been in the news business for decades, but the Duarteś sexenio was their prime time: they had up to 11 newspapers and one magazine; of these, only seven survived. Unmistakably, all are named El Heraldo. They have had editions in Xalapa, Veracruz, Tuxpan, Poza Rica, Martínez de la Torre, Coatzacoalcos, and Córdoba, which was a subsidiary established under the Duarte administration. In the chronicle of that day, March 21, 2014, state and federal officials were present. Cutting the ribbon was Antonio «Tony» Macas Yazegey, father of Karime, the then-governor’s mother-in-law, along with Eduardo Sánchez Macas, the man publicly leading the group.

The governor’s wife and the owner of the media conglomerate shared the last name. They are said to be cousins or distant cousins. Eduardo Sánchez Macas denied it when the Duarte government was staggering, but he has not shown birth certificates. Beyond the possible kinship, while being responsible for those newspapers, Sánchez Macías was also a local deputy, who in 2019 ended up in prison for the crime of «simulation fraud,» or assigning advertising from the congress to his newspapers.

Former Governor Miguel Ángel Yunes stated that between 2010 and 2016, the Duarte government awarded contracts worth 230 million pesos to his relatives, more than 11 million dollars, but the case of Grupo Editorial Sánchez has not yet been clarified. Whether or not related to the governor, there is still a conflict of interest: being a media entrepreneur at the same time as a deputy and, to top it off, being appointed back then, as secretary of the State Commission for the Attention and Protection of Journalists.

Eduardo Sánchez Macías’ political career includes wearing shirts of all colors: he went through the ranks of the PRI, then became a member of the Green Party of Mexico, then of Nueva Alianza, later of Movimiento Ciudadano, and currently, he has aligned himself with Morena.

Another politician and media entrepreneur is José Alejandro Montano Guzmán, head of Milenio El Portal, a newspaper that also disappeared mysteriously. Montano Guzmán belongs to a family linked for several generations to the security personnel of the PRI governors of Veracruz. He was a military man and the Secretary of Security during the six-year term of Miguel Alemán Velasco () , and he later studied public administration and law before fully entering the political world. He was a local deputy for the PRI (2004–2007) and a federal deputy (2012–2015) while leading the Veracruz branch of the newspaper Milenio. Gina Domínguez Colio, the strong woman of the Duarte government, who allocated the sizable advertising contracts, was the editor-in-chief of that newspaper and the editor was none other that the same journalist Víctor Báez Chino, who was executed.

These are just a few examples; they depict the blurry line between public and private in the media landscape of Veracruz at that time: government officials ran editorial outlets, others owned communications industries, and some politicians were shareholders or founders of newspapers. These connections conditioned and created dubious editorial commitments.

«My boss called me one day, very upset,» recounts a journalist from Xalapa. – «Hey, I heard you’re involved in that issue, right? Don’t you realize you’re hurting me? I have a deal here that could fall through if you continue with that. He told me to back off. “You better do it; otherwise, I’ve been told they are going to mess you up. I am telling you, I have direct contact with the state government.»

He recounts a time when he took part in a protest at the Congress, and the police beat him in front of the deputies, and how one of them, sitting on a bench, witnessed the abuse without saying anything. The same deputy held a leadership position at the media outlet where he worked.

To discuss the multimillion-dollar official propaganda contracts of the Duarte administration with media companies, it is necessary to mention the Capital Media Group, owned by the Maccise family. Founded in the 1980s by Anuar Maccise Dibb and inherited by his sons José Anuar and Luis Ernesto Maccise Uribe. They had 13 media outlets across the country, including television (Efekto TV), radio (Capital), and various specialized print publications such as The News and Estadio, although they only had one newspaper in Veracruz: Capital Veracruz.

There are documents showing that they owed nearly 8 million pesos that were allocated through their newspaper, Reporte Índigo. But they didn’t just receive advertising: in two direct awards, meaning without a bidding process, in 2014 and 2015, the Veracruz government bought 66 million granola bars, 47 million amaranth bars, and other NutriWell brand products from the Maccise Uribe brothers for a total of 191 million and 315 thousand pesos. According to Sebastián Barragán’s journalistic research, this purchase was for the supplies that would be delivered for school breakfasts in public children’s cafeterias.

The Maccise Uribe brothers, who were friends of former President Enrique Peña Nieto, received similar contracts for school breakfasts in the State of Mexico and are linked to possible embezzlement of up to one billion pesos. In addition, according to journalist Omar Fierro, both Peña Nieto and Emilio Lozoya Austin, former director of Petróleos Mexicanos, and other former high-ranking officials who are currently investigated for various acts of corruption listed their addresses at Montes Urales 425, the headquarters of Grupo Mac Multimedia and the Maccise Uribe law firm. The journalist, Juan Omar Fierro published.

A significant detail emerges: José Antonio García Herrera, a lawyer for Mac Multimedia, is the responsible editor of the newspapers of the Capital Group.

People who were media entrepreneurs were at the same time officials, and vice versa: the mass media are an endless revolving door for millionaire businesses in Mexican politics.

The scenario at the time occurred under the following circumstances: people with power used information as a way to steal funds, extort other politicians, support (or destroy) professions, and create low-budget rather than editorial projects. Interests were a priority beyond the news; the press was used as a tool for a channel of corruption. And in between, with meager salaries and many risks, journalists were trapped. At least four victims worked overtime in the companies, and the politicians mentioned: Gregorio Jiménez, Sergio Landa in Grupo Editorial Olmeca, and Víctor Báez Chino in Milenio El Portal.

5. The call

The phone rang and rang, but Gabriel Huge didn’t answer it even though it was right beside him. He looked worried. Mercedes, his aunt who raised him as her own son, looked at him strangely.

«Why aren’t you answering?»

«They’re calling me, but don’t worry, I’ll change the number.»

He did. On May 2, 2015, he already had a new phone number, but they found him anyway. He left saying he’d be right back, but he never returned.

Eventually, his family was able to reconstruct some of the events. That morning, Huge went downtown to cover a press conference, a routine procedure for police reports. His colleagues perceived him as calm; nothing unusual was noticed. Around eleven, he returned home with his family, where Mercedes and Isabel chatted briefly with him. His nephew, a fellow photographer, asked whether he had already been «there.” Huge replied,“I’m just about to go,» and departed without a motorcycle. They never knew where, but subsequently were informed: that he had been called to El Cristo. Antonio Rebolledo, a friend of his, informed the family that Huge had dropped by his business that afternoon, explaining he was heading to a delicate appointment and asking not to call or make a fuss, and added, “If I don’t return in two hours, take good care of my daughter.”

By the next morning, with no news, the family began to worry. Huge didn’t answer his phone, and he didn’t show up. The authorities announced the discovery of four bodies, two of them were the uncle and nephew.

Mutilated. In garbage bags and thrown into a sewage canal called La Zamorana.

It was May 3, 2015, the Freedom of Expression Day.

People smiled when they heard of Gabriel Huge; nostalgia welling up, followed by sadness, perhaps by his premature death or the way he was killed. «Uge» is pronounced as it sounds in Spanish. He was well-known among the police beat. They called him «el mariachi» because, in his early days as a photographer, he carried a Pentax SLR inside a violin case, the only thing he could find to protect it from the bumps and jostling of chasing stories 24/7, at accidents or deaths.

– “100% police beat,» recalls Horacio Zamora, also a photographer. «He was in the thick of it, the first to arrive but also the one who shared his photo with those who couldn’t make it on time. He gave advice, and everyone listened. He was a leader.

Mariachi, a 37-year-old photojournalist, covered crime stories for over a decade. His pictures would appear every day in the «Sucesos,» the most-viewed section of Notiver, the most popular newspaper in Veracruz back then.

When Huge’s colleagues and friends Milo Vela, along with his son Misael López, and his son’s mother, Agustina Solana, were killed, he was deeply affected, like much of the press in Port City. A month later, another colleague, Yolanda Ordaz, from Notiver, and the third killed from the same outlet, Huge, decided to flee. He was part of an exodus of displaced reporters—those who sought refuge as best they could or left journalism to dedicate themselves to something else. An nearly invisible exodus tha is poorly documented and a time that some refer to as the “withdrawing”.

Huge went first to Tabasco and later to Poza Rica, where colleagues remember him fondly because he gained sympathy, even though his stay there was short.

«He gave me a photo gallery as a gift and left me his Nextel phone with all his contacts; he seemed very worried,» says Lydia López, a journalist and teacher in the northern area.

He had never worked as a radio broadcaster, but he did it in Poza Rica. He was the enterprising kind who wasn‘t afraid to try new things. In addition to reporting, he spent time in pawnshops, checking what he could get. That’s how he found several computers and decided to open a cybercafé, recalls Isabel Luna, his niece, though they were like brother and sister.

«Well, I’m not sure if the cybercafé came first because he also opened a video rental store, we rented movies. Then he started buying tires, wanting to open a tire repair shop. That’s how he was. That’s how many journalists back then and in the present were, with no option but to have multiple jobs to make a living. Like Pedro Tamayo Rosas, with his food stand, or Sergio Landa, a former soccer referee, and Juan Atalo Mendóza Delgado who drove a taxi.»

After the murders at Notiver, there was an implicit ban on hiring anyone who had worked for that outlet in the port area. The media wouldn’t hire them, claiming it was out of fear of reprisals. Isabel remembers that her uncle had a project to start a newspaper, and it was well underway; he had even chosen a name: El Regional de Veracruz. It was a joint project with his younger brother and Ana Irasema Becerra, who worked selling advertising for the press. The three of them, along with another photographer Esteban Rodríguez, were found murdered on the morning of May 3rd.

– Why were they killed?

– We don’t know. We still don’t know – Sitting under a guava tree that has been the site of conversations and parties for decades, in the courtyard of the house they live in the neighborhood of Icazo, Isabel and Mercedes respond with their eyes downcast. The courtyard where they also mourned for Gabriel Huge and Guillermo.

Duarte came to tell us that there would be an investigation, but nothing has happened. Duarte only came to take a photo.

While the family was grieving, the authorities tried to navigate scandal after scandal. A week earlier, Regina Martínez had been murdered, and a few months before that, three other journalists from Notiver (Milo Vela, Misael López, and Yolanda Ordaz) had been killed. At Acayucan, Gabriel Fonseca, another journalist, had also disappeared, although no one spoke about him.

Simultaneously, the former federal prosecutor for crimes against freedom of expression, Laura Borbolla, arrived at the port to open the preliminary investigation AP/35/FEADLE/2012. There were condolences, flowers, and statements full of promises for justice. They offered protection to the family, taking them out of the state for their safety. In white vans escorted by patrol cars, Mercedes, Isabel, and their children were taken to the state of Puebla.

There, they were kept safe for only a week, before being returned to their same house.

Guillermo, known as Memo to everyone, was serious since he was a child. Isabel, his older sister, says that in childhood, he didn’t play much, he just ran in the courtyard. He had a sense of responsibility, and she believes that perhaps he would have liked to study, but chose to work, he felt compelled to support the household expenses after their mother, Mercedes, became widowed. Later, when Isabel got divorced, it was Huge and Guillermo who took care of buying diapers, milk, and everything else needed for their nephews.

Memo completed the basic education, choosing technical training in air conditioning repair, but as soon as he finished his classes, he hit the streets to work as a journalist. Close to his uncle Gabriel Huge, who was already an experienced crime photographer and undoubtedly his role model in everything. After getting the pace of reporting, Memo soon realized being a beat reporter was his calling. He only had the chance to work for two years, but they were very intense.

Makanaki has several photos of Guillermo on his phone. You can see him standing guard at a car crash scene. Another one outside the prison, at the “base”, is what the crime reporters call the place where they waited for news.

Memo was a wild one; he loved to have a good time. He didn’t pay much attention to his work because he was always goofing around with those around him. Memo was around five feet nine. Despite being a bit of a mess, he was very dedicated to his work. When it was time to work, he gave it his all. I can assure that, because a few times I told him, “Hey Memo, are you going to the accident scene? Yes,” [he responded]. – “Don’t be mean; cover it for me; I don’t feel like going all the way there. – Okay, I’ll give you some photos” [he replied]. And off he went to take some really good photos. I can’t say Memo, Mariachi, or Esteban Rodríguez were lazy. They might have been cheerful and wild, but I can’t tell you anything bad about them. They always performed well with the rest of the group and with us.

Makanaki is a well-known photographer in the port. He’s in his sixties now but still rides around on his motorcycle, wearing his journalist vest and his camera hanging. It saddens him to remember Guillermo as such a happy person and thinking he was killed at such a young age.

– He was still so young. He was so young, as crime reporter, he had so much in front of him.

Guillermo was 21 years old.

His Facebook profile is still active, and messages are frequent. His sister Isabel, his girlfriend Tania, and his friends continue to write on his wall. People congratulated him on his birthday and mentioned they loved and missed him.

In the photos he uploaded, he looks good with sunglasses, in selfies, and with friends. Isabel says he was into reggaeton and salsa dancing.

– We hardly ever went to parties together. We went to a cousin’s quinceañera once; we were already there when he finished work. I remember dancing with him; I think it only happened twice because we hardly ever danced together, says Isabel..

They danced in the courtyard under the guava tree.

In Veracruz, and perhaps in several states, the cartels’people call newsrooms to say what should be published and what should not. They call the directors, journalists, and photographers; calling to give tips about something that happened or is about to happen—tips that more than help—are instructions for mandatory coverage. In 2010–2016, there were instances when tips came so quickly that they led to absurd situations, such as journalists showing up before the corpses were even dumped at the scene.

The narcos call because they have phone numbers. When there’s a new “plaza boss”, one of the first things they do is acquire data [names phone numbers, addresses, etc.].

They call, but frequently don’t even need to introduce themselves; everyone knows who they are. They are spotted on the street, recognized, and greeted. Often, especially in small towns, the new chief of the plaza was formely the municipal policeman officer or the traffic cop. He used to be your source, the one who gave you tips, and whom you interviewed until yesterday. And besides being a narco, he’s a neighbor; he lives two or three houses down from your house. Or you went to the same school; he’s your childhood friend, your cousin’s husband, or even your compadre.

The phone rings; how can you not answer? Does it serve any purpose not to answer?

What this investigation has found shows that the categories of pressure or collusion are ambiguous in the Veracruz of 2010–2016: there was an inevitable, often forced, and always unequal contact.

They called Gabriel Huge in Veracruz in May 2012. He left without saying where he was going, never coming back: they found pieces of his body in garbage bags.

They summoned Noel Lopez Olguin in Jáltipan, but he said he was heading to Soteapan and that he would be back in the afternoon. It was March 8, 2011. Three months later, they found him in a clandestine grave.

They called Sergio Landa in Cardel on January 22, 2012. They called him every half hour, and he turned pale. He rushed out, saying, «I’ll be right back; don’t turn off the machine; I’ll be back to finish what I’m doing.» According to people who have read the court records, security cameras recorded him arriving on his motorcycle at the Tamarindos gas station, where he met state police officers. Sergio followed the patrol car, and they arrived at a diner on the Conejos-Huatusco highway. He left his bike and followed the police officers on foot towards Huatusco. Nothing has been heard from him since.

They called Miguel Morales on July 19th, 2012, at the Diario de Poza Rica offices. There was tension over a story he covered the day before: a girl drowned in the Cazones River. It was an accident, a local and normal piece of information, recalls a colleague from that city who asked not to be named. The night before, someone warned not to publish the information, and although the Diario de Poza Rica deleted the text before sending the edition to print, it was published and signed by Miguel Morales in another local media outlet, Tribuna Papantleca. His colleagues believe that this story was the reason for Miguel Morales’ disappearance. He had been a self-taught crime reporter for a short time. He was paid 40 pesos per story, which is why he published in several places. On that Tuesday, July 19, he received the call, left his equipment at the newspaper reception, and left. He hasn’t returned.

Four of them received the called, perhaps others did too.

6. The Police, The Journalist by Trade

– What aren’ t you allowed to say?

– About crime reporting.

Hugo Gallardo responds without hesitation. He is precise in his words, with the measured pause and histrionics of a seasoned television journalist, because he has 36 years of experience. For a long time, he was the face of Televisa in the port of Veracruz. He reported on crime, which became almost the only thing that area contributed to the national agenda: massacres, 35 bodies dumped in a roundabout, corpses upon corpses. These were times when the homicide rate in the state reached 23.5 victims per 100,000 inhabitants, which the World Health Organization considers akin to an epidemic of violence because 10 is the limit for what is considered normal.

Gallardo is tall, bronzed, and has a perfectly trimmed mustache. His pants are pressed, and his shirt is so white it dazzles. He is preparing to start the noon newscast on his own radio station, which he started as a means of survival after the misfortune of being added to the list of those blacklisted from print media.

Even in front of the cameras, he names politicians and cartels without euphemisms; he has lost the fear of naming them. What cannot be talked about, he says, is the police source. Because the greatest risk is being identified with that work. He knew it well when he was kidnapped after reading on the air a brief note, just three lines, saying that bloodstains were found inside a car. Because of that routine broadcast on Televisa, he was taken, beaten, and tortured in a manner so common in the port that it now has a name: «tablear.» Kidnapping. Beatings. Torture. Humiliation, and then the aftermath, stigma.

«In some places where I applied for jobs, they responded that there was an order from the governor not to hire me.»

The strategy was completed with another defamatory tactic: blacklists. New lists were constantly said to exist, and the names of journalists were circulated through social networks. Other times, there was simply a list without details, a rumor that many suspected came from government offices.

No one trusts anyone anymore. Distrust was sown. But even more, distrust was directed towards crime journalists because it was they who were being killed—the perverse custom of being murdered and still being considered a suspect in your death. The prejudices of ‘they must have done something,’ ‘they were involved in something,’ echoed endlessly.

Being a crime journalist became a risk in itself. Out of the 20 murdered and disappeared, 14 were dedicated to police information (only Regina Martínez did not cover it, and five others had done so sporadically or focused on other topics: Noel López Olguín, Rubén Espinosa Becerril, Moisés Sánchez, Armando Saldaña, and Manuel Torres González). In addition, among the 20 who disappeared and were murdered, 17 were self-taught.

Covering crime news always entails risk. It involves dealing with dangerous sources, getting caught in the crossfire, and navigating crime scenes. But the danger for the press deepens when thousands of readers want to see details of the dead, the faces of the victims, and the dripping blood. People like to see blood, several journalists say. In everyday work, this translates into the obligation to cover every violent event because the boss orders it because all the stories are needed for the newspaper to sell. Those who don’t take risk, losing their jobs.

More blood generated better newspaper sales and greater bargaining power for news companies with the government. Because the media outlet was successful and widely read, it was a good showcase for advertising, or because the authorities claimed to inhibit the publication decrease the current violence and “prevent its spread”. Crime news became a crucial space where what was happening was shown, unfiltered. And that was a double-edged sword.

– People consumed a lot of blood (…) Newsstand vendors had meetings to let you know that you had to use the bloodiest photo; otherwise, they wouldn’t sell. Whoever managed to have the bloodiest, most impactful photo was the one who actually sold (…) The newsstand vendors would tell you, “Can you provide coverage about the cartel’s dead person? Because people want to know about it.” So, there was a conflict between what the market demanded, so to speak, and what happened at an ethical level vs. what the criminals wanted. Obviously, they didn’t want to show that they were at war and that they lost on some occasions, so they would directly contact newsrooms.

Sayda Chiñas is a journalist from Coatzacoalcos and one of the few people willing to speak openly in that region of water, oil, and fear. She was a colleague and Gregorio Jiménez’s supervisor. Chiñas was also aware of the circumstances at the time because she was part of the State Commission for the Attention and Protection of Journalists, the CEAPP.

Tall, strong-willed, and outspoken, Sayda was the one who took action when Goyo was kidnapped. She alerted colleagues in the capital city to make the news national and to pressure for the reporter’s release. Both authorities and media executives intimidated her, threatened her, and wanted her to stay silent. She resisted the pressure and continued to demand justice.

Years later, she summarizes what she witnessed clearly after the kidnapping and murder of her colleague, Gregorio Jiménez. How businessmen, executives, and media owners viewed journalists:

The issue is that they see us as replaceable; there will always be a new journalist doing the same work for less money. What they were doing was cutting reporters’ expenses. Moreover, some media outlets were being endorsed by the municipalities; what this means is that they would tell you, “I am not who pays you; though you need to send me the work, the municipality of [such and such place] will pay you.» [We’ll omit details to avoid putting her at risk.]

Another turn in the power of agreements. But above all, several colleagues say, media outlets took advantage of the so-called «reporters by trade» to compete and sell more among the media outlets. These were individuals who didn’t have the opportunity for formal education but gained experience solely through fieldwork. When the situation became a dire, seasoned journalists put up some resistance, saying, «I won’t do that» or complaining that their writing was altered. In response, bosses turned to people desperate for work and exploited their lack of knowledge and even their desire to stand out.

In exchange for meager wages—20 to 40 pesos per article—they were sent to cover the most complex events, also exploiting their legitimate personal ambitions. Working in police reporting meant assuming an attractive position: they became the most read and recognized individuals in their communities, the ones who told the truth about what was happening.

These were the cases of Gabriel Fonseca, a 17-year-old who reported on police matters in Acayucan (2011), or Miguel Morales, who went from cleaning worker to police reporter in Poza Rica (2012), and Sergio Landa, formerly a painter, sign maker, and soccer referee, who became a reporter in Cardel (2013), as well as Gregorio Jiménez, who covered police news after being a social photographer and construction worker (2014).

The youngest and the ones most were sent to a front, difficult to control, even for those with formal education. They were sent to the work field by editors, directors, and bosses, just thinking of the cover that would sell the most, but without any guarantee, protection, or support for the reporters.

Something similar is happening today in the battle for likes. Live broadcasts on Facebook and social media have become extremely popular and even massive, with thousands of people watching crime scenes live. And while it’s profitable because pages like «Veracruz on Alert» already have many advertisers, everything indicates that live streaming is the new crime news.

The police reporter emerges out of necessity, but also out of enjoyment, no one denies it.

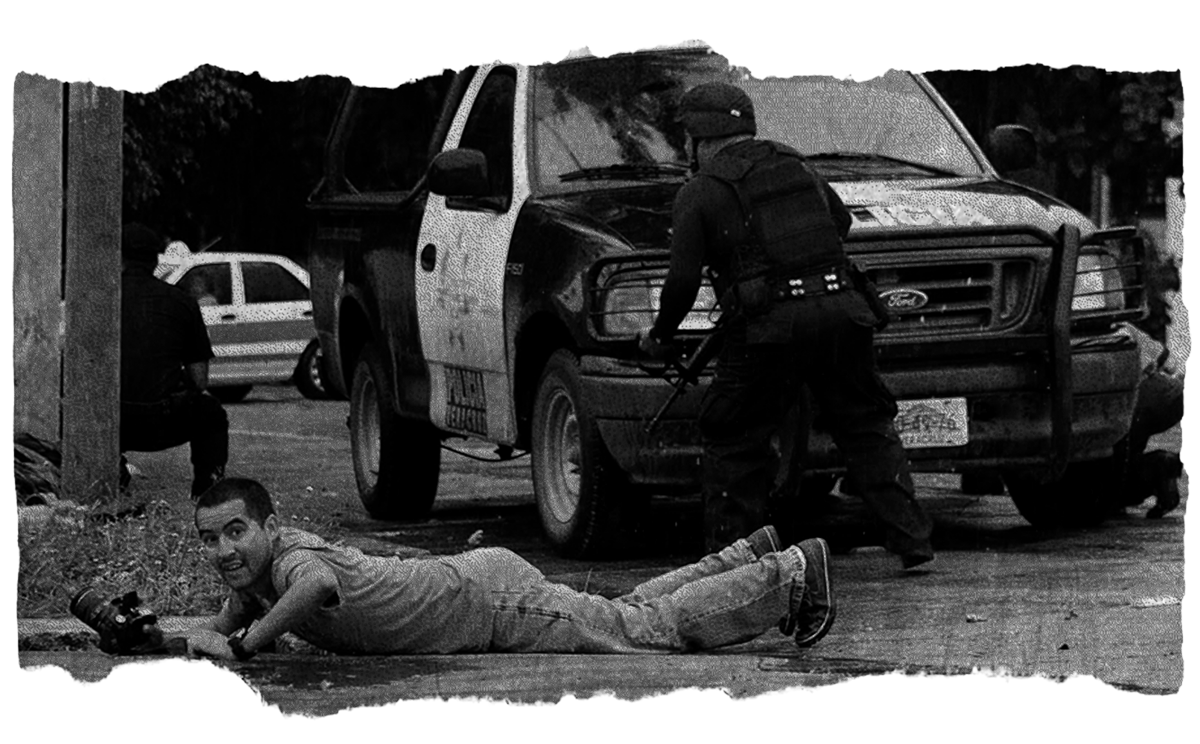

Smiling like kids who’ve pulled a prank, some reporters convince themselves that it’s a sort of addiction. The thrill of outrunning ambulances at top speed, the pleasure of taking the best photo exclusive, and the competition to make the front page or capture the picture that will go viral. Crime reporters acknowledge that they are brave and even cunning, but it’s evident that this profession has become excessively dangerous—almost like receiving a death sentence. It happened without warning. Many didn’t realize what was happening. Of the twenty people who were killed and missing, only Regina Martínez had decided not to cover anything related to police matters.

– You didn’t know where the hell the punches were coming from, as described by cartoonist Rafael Pineda, known as Rapé. The worst panic attack was not knowing where the violence was coming from. He also fled the country and later moved to Mexico City to sleep more peacefully.

In a state embroiled in a battle for control, in a territory where cartels, police, politicians, and businessmen were in dispute, being a police journalist meant being caught in the crossfire. Gunshots came from the drug cartels but also from vague enemies, those who one day were allies but the next switched sides. It was a blind shootout.

7. Death Forms

On that night, it had gotten a little later than usual; it was past eleven, and Víctor Báez Chino was just about to leave the newsroom. He was the director of Reporteros Policiacos, a portal founded by pure journalists that, in less than four years, had managed to sustain and grow. They started with a bi-weekly edition, then made it weekly due to demand from readers, and they got sponsors for advertising sales, no longer depending on agreements. Everyone in Xalapa read them. Colleagues from various regions called, asking to collaborate even without pay.

It was an unusual but understandable success: violence generated a lot of information, audiences wanted to consume it, and moreover, several experienced journalists came together in the new portal. Víctor was the leader of the project. He had 25 years of experience, having worked for various media outlets such as El Diario de Xalapa, AZ Diario, El Martinense, El Sol de Córdoba, and at that time, he was also the editor of the police section of Milenio El Portal, the Veracruz branch of the national newspaper Milenio. Additionally, Víctor was one of those people who rallied others around him, who summoned and organized (just like Rubén Espinosa Becerril, another victim).

That night, Víctor was delayed in leaving because an assistant, his niece, asking him to do a few things. There were still several workers in the offices. At 11:30 PM, they all decided to leave; the workday of Monday, June 13, 2012, was considered over.

As soon as they were outside on Chapultepec Street, a gray van arrived. Armed men got out. Of all those present, who were five in total, only Víctor Báez Chino was taken away.

Four hours later, around 4 am, they left his remains on the street. His mutilated body inside a black garbage bag. In front of the IMSS offices and a few blocks from the Government Palace.

– Each situation of violence against journalists was unique,» says Noé Zavaleta, who has worked as a reporter for more than ten years. He says this to avoid simplistic explanations, and from falling into superficial analysis, and sole responsibility. He assures this since he knows well both Xalapa, where he was born, and the state where he lives. Zavaleta is right: only in Xalapa do you feel the weight of the political capital, surrounded by ears that observe in detail or those who take note of everything and ask questions when you take out a camera. It is different in Veracruz-Boca del Río, the economic capital, where the territorial dispute over conquering a port that moves all kinds of goods is still perceived through gunfire and blood. The problems in Coatzacoalcos are different, which has suffered an epidemic of oil worker kidnappings who earn good salaries. The zone has not been able to control extortion because they say that no one, not even the largest petrochemical company, signs agreements without the approval of the zone chief. The reign of terror and silence in Poza Rica is also different; it is a declining oil region, too close to Tamaulipas and the route to the United States, where few dare speak.

About the crimes against journalists in Veracruz, there is no single explanation, no single executioner, or a single way of killing. But there are some coincidences and patterns that, if not general, are repeated in several cases.

For example, 12 out of the 17 journalists murdered had previously disappeared for hours, days, or months. And if we add the 3 who disappeared, it turns out that 15 out of the 20 victims disappeared. Disappearance has been a constant, either as a precursor to murder or as a continued fate in the present.

We don’t have details of how that precise moment happened in all cases, but among those for which we do have information, 9 were kidnapped in public places, 3 in their homes, and one at the entrance of the media outlet where they worked.

Gregorio Jiménez was taken in the morning as he was getting ready to take his children to school in Villa Allende, near Coatzacoalcos. Five men came to his house in a single van. They had long and short firearms. They said, «this is the photographer.» They pointed a gun at one of his daughters, so he did not resist.

A larger group of 9 or 12 people aboard 5 vehicles arrived at Moisés Sánchez’s house in El Tejar, Medellín. They were armed with long guns. They asked for him. There was no room to resist; they took him by force in front of his family, who could do nothing. They also took his camera.

An armed commando took Anabel Flores from her home. They were men in uniforms «like soldiers» with long guns, helmets, vests, and balaclavas, her family recalled. It was two in the morning. She was already in bed, in her pajamas, taking care of her newborn baby; when they dragged her away.

Regarding the murders, little is known about the details at the moment they were deprived of their lives. But only 3 out of the 17 cases occurred within homes.

Regina Martínez was murdered in her home in Xalapa. It is not clear what items were taken or if any work materials were missing, especially because it is presumed that the crime scene was manipulated. The government quickly suggested the hypothesis of a crime of passion, which it has maintained to this day, although her colleagues say that the murder is clearly linked to her journalistic work, and she herself had asked her family to keep their distance because she was investigating something important.

Three members of the Velasco-Solana family were attacked inside their home in Veracruz. In various ways, with several weapons and in separate rooms, they took the lives of Miguel Ángel, his wife Agustina Solana, and their youngest son, Misael López, aged 21. Both Milo and Misael were journalists.

Photographer Rubén Espinosa was murdered in Mexico City inside the apartment where activist Nadia Vera lived. Both had fled from Veracruz due to threats, and both were tortured. Three other women who were in the place – Mile Virginia Martín, Yesenia Quiroz, and Alejandra Negrete -, were killed earlier and in a different way.

In all three cases, everything indicates that the attackers spent quite some time inside the homes. They did not kill the journalists quickly or with a single shot. There were signs of torture with various objects. These were planned operations in which several people participated. The attackers also made phone calls to other people. Outside the Velasco-Solana’s home, for example, there were several trucks. And in the Narvarte neighborhood, where Rubén and Nadia were killed, there were cars waiting.

Two other victims were executed on the street.

Manuel Torres González was killed on the morning of May 15th, 2016, on 2 de abril street, in an affluent and theoretically safe neighborhood, in front of a clinic and near the transit offices of Poza Rica. He was killed with a single shot to the head. «It was very precise and done by a skilled shooter,» say his colleagues.

Pedro Tamayo was shot more than ten times with a 9mm weapon at the door of his house one night in July 2016 while attending the hamburger and hot dog stand he had set up with his family. The police, who allegedly guarded him, were just a few meters away but did nothing. The ambulance took a long time to arrive. Before being taken to the hospital where he died, he said to his wife, Alicia Blanco:

«Don’t let them take me to social security, honey. The state police will finish killing me there. Take care of my children, my grandchildren, and resign from the state security.»

8. Infiltrating pain (and terror)

Injuries to the body and head with a blade.

33 shots on 3 bodies with 9mm, .38 Super, and .380 caliber weapons.

The body showed evidence of torture and was decapitated.

A wound on the cheek, three holes apparently caused by a blackjack glove.

The legs detached and severed.

Blows to the body.

A gunshot to the head.

Found semi-naked, bound, and the head covered with a plastic bag.

Bruises on the back.

12 stab wounds.

Various injuries and lower limbs dismembered.

Seated, with a disfigured face.

Tied up with gray tape on the upper and lower limbs.

Had bruises on the body and fists tied behind the back.

Blindfolded with blows all over the body.

Burns and abrasions on the neck. Presumably first strangled, then decapitated and mutilated.

Lying face down in a pool of blood.

Decapitated body, with signs of torture, and the head separate.

His hands were tied behind his back. The corpse was held in a «sitting position».

He died from a blow to the head.

Asphyxia by suffocation.

Anoxia from strangulation.

Drowned with a bathroom rag.

Hypovolemic shock produced by amputation and decapitation.

Dismembered tied by the thorax and abdomen with a nylon rope.

Cut tongue and post-mortem dismemberment. The tongue was not found.

The head was severed. The remains were left in bags in front of the offices of a media outlet.

Tortured and shot 4 times in the back of the head.

Found in a clandestine grave inside a safe house.

They cut off one ear.

The arms were severed, the hands were separate.

Skinned, removed from the face and part of the neck.

The bodies had been executed with a coup de grâce.

Found in a field.

The body was found on the road.

Remains found in garbage bags on the street.

Semidressed, tortured, and blindfolded.

That’s what happened to the 17 journalists murdered in Veracruz from 2010 to 2016. It’s not necessary to disclose their names or which torture, mutilation, or dismemberment corresponds to each case; it is enough to know that this is what happened during the crimes perpetrated. These are not invented words, but information scraped from files, excerpts from death certificates, and details leaked to the press. Words that refer to people, their bodies, and their lives.

Two victims were suffocated or drowned, 6 were shot, 7 were decapitated and dismembered. Of the 17 homicides, only in 4 was death caused in a single moment; in the others -13- we find that only in one case there is not enough information, and in 12 remaining cases the victims showed signs of torture.

We still don’t know what happened to Gabriel Fonseca, Miguel Morales, and Sergio Landa because they are still missing. Nor do we have details of what happened to Noel López Olguín because his body was found three months after being buried, already without the possibility of a clear autopsy.

Additionally, there are recurring elements in the crime’s third phase: disclosure. Of the 17 murdered journalists, only two were buried or deposited in non-visible places. Fifteen, were thrown in public places with the clear intention of being found. Sometimes in garbage bags, other times with cardboard signs or thrown on the ground. In downtown areas, in front of media outlets, on freeways, and at the side of the roads. Their bodies were almost always mutilated, thrown, and exhibited as messages of terror.

In Veracruz, journalists were not only murdered: they were tortured first and then their mutilated bodies were exhibited. The methods convey messages.

First came control; with agreements, there were calls for instructions on what is or is not published. Then, sow distrust with blacklistings and rumors of who’s involved. Kidnapping, abducting, and beatings were ways to teach a lesson: “We are in charge here». Interrogation and torture were forms of intimidation but also to obtain information because journalists “know things.”.

Their methods of terrorizing were torture, murder, and displaying bodies in pieces. That could summarize the manual on violence against the press in Veracruz from 2010 to 2016. At the national level, media outlets already have a kind of routine coverage when a journalist is killed: the name, what number is on the list, and some details about their career, among other details.

Many of us may not have disclosed the details of the crimes because, either from outside, we didn’t know them or perhaps out of decency or ethical obligation. However, within Veracruz, every murder’s specifics and action taken against each victim are well known. These were warnings: “This can happen to you if we catch you.» That is how the silence sounds.

In his book «Reguero de Cadáveres,»(Domping of Corpses) Juan Eduardo Flores Mateos recounts a scene that clearly illustrates the effect of these messages. It happened during those years at a meeting of journalists convened by Pie de Página, attended by some Veracruz reporters. Daniela Pastrana, «who had ties to international organizations aiding journalists at risk, asked Nacho [Ignacio Carvajal] what he needed to better cope with coverage in the Port of Veracruz. “A gun,” Nacho said. “I need a gun.” Pastrana nervously smiled. In her friendly tone, she retorted to Nacho, asking what good a small pistol would do against the weapons used by drug traffickers. “I want a gun so they don’t catch me alive, Pastrana.” Silence fell over the table. Then Nacho continued. “Have you seen how those people torture, Pastrana? They’re primitive, rudimentary. They use hammers, screwdrivers. I want the gun in case I get caught; I’d rather shoot myself before they take me away.”

Javier Duarte is in prison, as well as Marco Conde. Bermúdez Zurita, Gina Domínguez, and former prosecutor Bravo Contreras were also incarcerated, but they regained their freedom. And although nearly ten years have passed since the end of that administration, everything in Veracruz remains very similar.

Journalists don’t answer calls from unknown numbers. To contact them, it’s necessary to first message them via WhatsApp, introduce oneself, and have the recommendation of someone they trust. Only then do they agree to speak briefly, perhaps for an interview.

Many accepted to meet, but at the last minute, they cancelled. «I have nothing to contribute» was the main explanation. Those who spoke out were affected; there were topics they simply couldn’t address; they cried or trembled in terror or anger. They requested anonymity for security and asked, «I only talk off the record; don’t even use my voice, or if you want to use it, it has to be distorted.»

No matter if the interview was anonymous, most did not mention the names of former officials, businessmen, or drug traffickers. They didn’t give surnames or identities; they described or used other details to imply whom they were referring to. If you completed the sentence with that name, they only nodded with a slight smile of satisfaction, indicating that you understood more or less how things stood. If you said something absurd, they didn’t deny it; as if no one should have any knowledge of what they know.

When talking to journalists from that area, it is like constantly speaking in codes, as if the walls had eyes and ears. They live in a constant state of distrust, as if in a war.

With the families of murdered and missing journalists, the situation is also complicated. The terror is just as present as in the first hours of the crimes. Some families agreed to give interviews only to build a biography, but seven families completely refused to participate.

They do not want to share data or even memories of their childhood. They fear that any details given or, if seen, giving interviews could mean putting themselves at greater risk, causing a stir, and they could be exposed. They are not exaggerating; in some places, killers are still active, have been promoted, or are now more powerful than before.

– «The one who ordered Cuco Fonseca’s disappearance is now a plaza boss.»

– «We were attacked by crime at the government’s request.»

– «We continue to walk in a mined world.»

These are the words of three journalists who requested that their names were hidden. Jorge Sánchez, son of Moisés Sánchez, has said tirelessly in recent years that the former mayor of Medellin, who is suspected of killing his father, goes around in public and gets away with it.

The relatives are also angry. They feel mistreated by the press, by colleagues, friends, and neighbors. By those who spoke (and still speak) lightly of their loved ones.

For example, one of them said, «Based on the experience we had, we don’t even want to name that situation. The unfair accusations and what people have said have hurt us a lot. And now that their son is starting to realize everything, we don’t want him to go through what we went through.»

The message comes via WhatsApp. The aunt of one of the murdered journalists writes. She is friendly and affectionate; she engages in dialogue for months but does not want to be involved in making any public statements. Like her, several people explained their reasons for no longer participating in anything, in any memory exercise, or even in any demand for justice. Others said no, thanks, or did not even respond.

De las 33 personas entrevistadas para este reportaje, la mayoría pidió anonimato.