Context

Context of Lethal Violence in Veracruz 2010-2016. Summary

By María Eloísa Quintero

Murders and massacres on the rise: Veracruz also suffered the escalation of violence since the first years of the 21st century. And the so-called war against drug trafficking was a scenario from which many took advantage. With new security corporations, federal alliances and a much larger budget, corruption cases escalated. In some areas, fighting crime was the perfect alibi for the diversion of funds. And in the midst of this, violence against the press: at least 17 journalists murdered and 3 disappeared in the period 2010-2016. Reporters trapped in a web that crosses the public with the private, the government with crime, crime with information.

Here you will find summarized fractions of the context analysis of the Veracruz case 2010-2016, a case study to try to understand the lethal violence against journalists in the context of a general context with political, economic, criminal and various power circles dimensions.

General political context

For decades, Mexico’s democracy had no alternation: the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) ruled uninterruptedly from its foundation in 1929 until 2000, when the National Action Party (PAN) won the elections with Vicente Fox as president; he was succeeded by Felipe Calderón (PAN) in 2006.

At the local level, such national political changes were not always replicated. As far as Veracruz is concerned, the state continued with its PRI tradition until 2016, when Miguel Ángel Yunes Linares won the gubernatorial elections as candidate of the PAN-PRD coalition.(1) However, it goes without saying that this politician came from the ranks of the PRI until his definitive jump to the PAN in 2005.

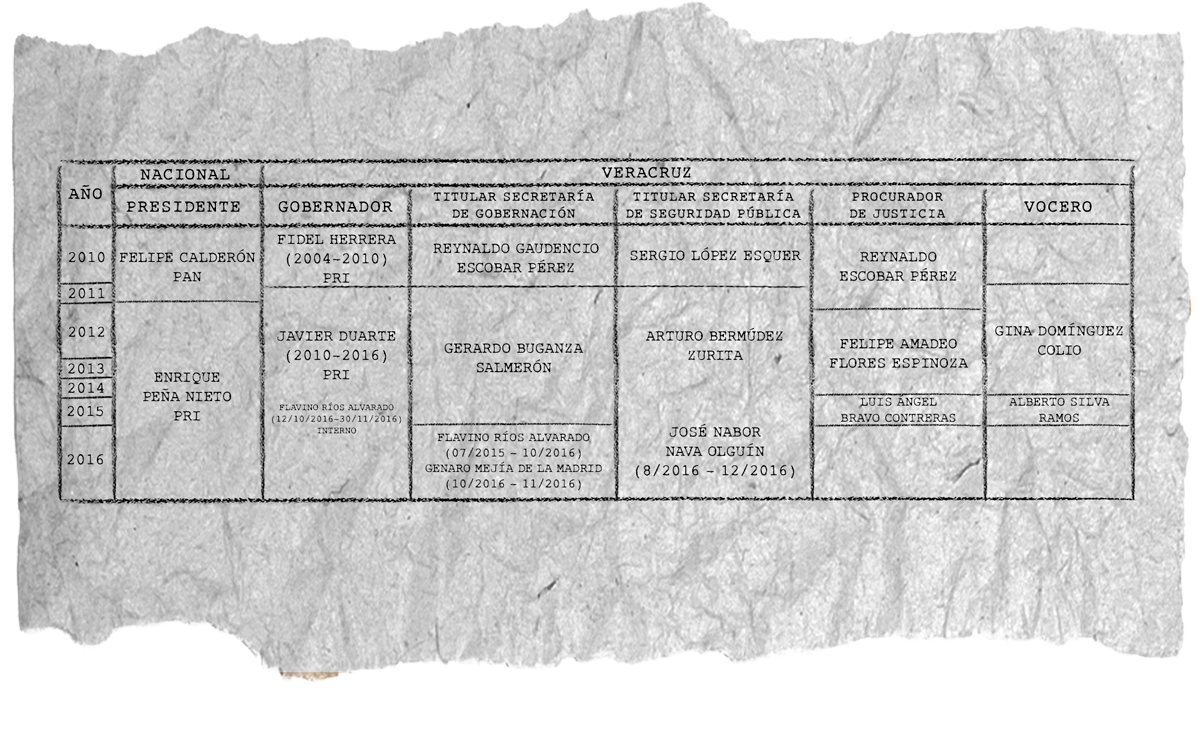

In the period under study (2010-2016), Javier Duarte was in charge of state politics. During his government he had several secretaries of the Interior, three attorneys general, two spokespersons and two Secretaries of Public Security -one of them for almost the entire period-.

When investigating violence against the press, two officials are the most named: Gina Dominguez Colio and Arturo Bermudez Zurita; the former had so much power that she earned the nickname “the Vice”; the latter was known as “Captain Storm”.

Violence and public security policy

In Veracruz there was a sharp increase in violence since the first years of the millennium, but especially since 2009 when the homicide rate shot up from 5 to 10 per 100 thousand inhabitants to reach 20.56 in 2017.

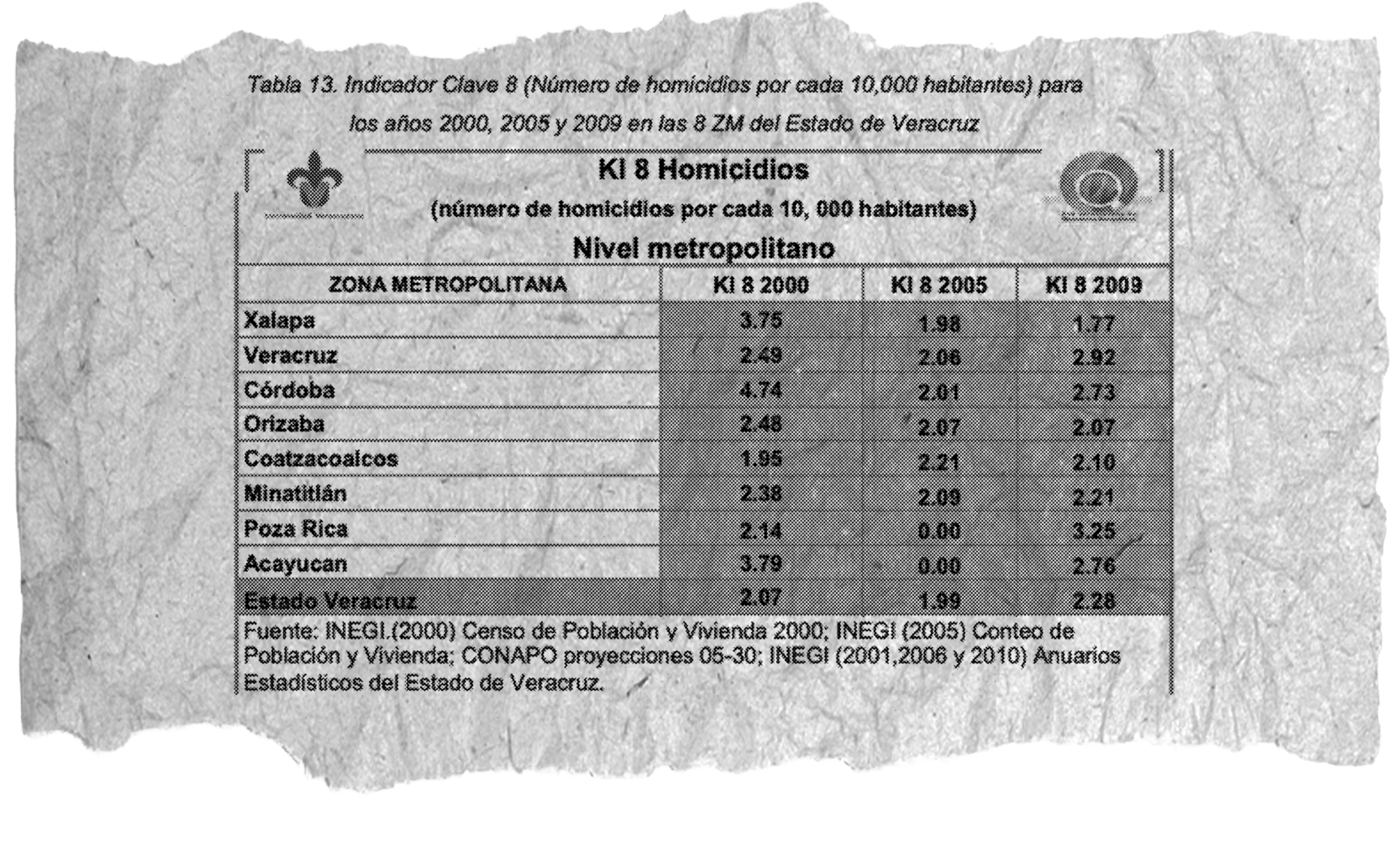

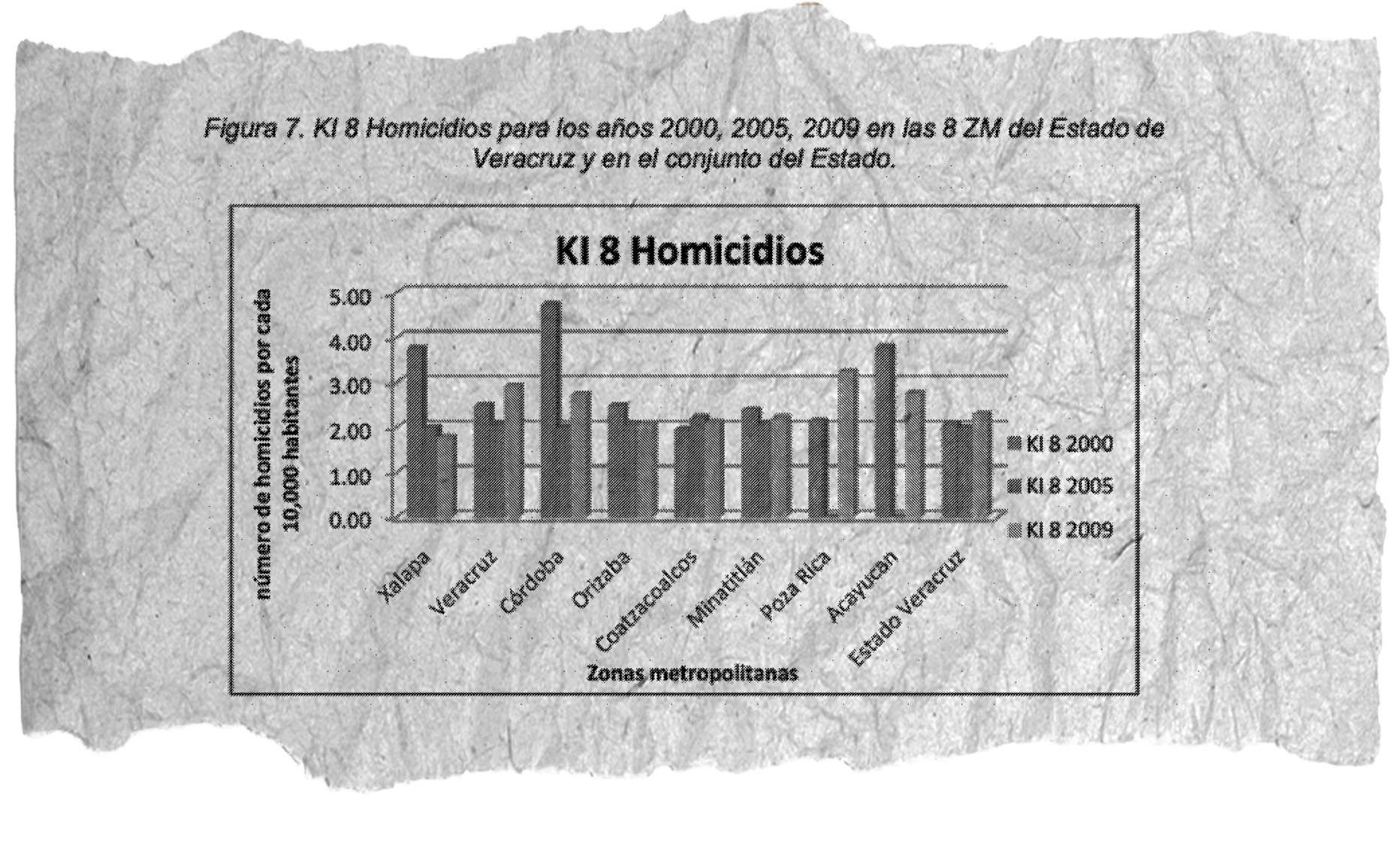

CHART 1 – REPORT OF UN-HABITAT INDICATORS IN VERACRUZAN CITIES PERIOD 2000-2010.

The situation developed in stages. In 2000 some regions and cities of Veracruz reached high homicide rates, among them Poza Rica and Xalapa.(2) In 2004 Fidel Herrera Beltrán became governor for the PRI. At that time certain criminal acts began to have repercussions.

CHART 3- REPORT OF UN-HABITAT INDICATORS IN VERACRUZAN CITIES PERIOD 2000-2010

One of the most shocking events was the murder of journalist Raúl Gibb, owner of the newspaper “La Opinión” of Poza Rica -April 8, 2005-, homicide that was related to his writings about the looting of Pemex pipelines by a group linked to the Gulf Cartel. But the expressions of violence were many: disappearances of migrants, murder of journalists, extortion and kidnapping of ordinary citizens, repression of students and other demonstrators.

Meanwhile, in the national context, President Felipe Calderón (PAN) declared war on drug trafficking(3) and used the Army and the Navy to fight it. As a consequence, the budget allocated for public security and national defense was increased exponentially, and what was called “single commands” was created: a merger of police and preventive units into 32 single commands that were in charge of the Public Security Secretariats of each state and that acted in coordination with federal agencies. In return, the states that adopted the national government’s security strategy received more federal resources to equip, train, evaluate and strengthen state and municipal police forces.

Veracruz’s cooperation with the federal government in the so-called “war against drug trafficking” was strengthened through the signing of agreements between the Public Security Secretariat (SSP) of Veracruz and the Armed Forces to carry out joint operations under the Single State Command. At the time, the SSP was headed by Arturo Bermúdez Zurita, who was later (2017) arrested for illicit enrichment, accused of influence peddling and abuse of authority; a year later he was also indicted for cases of forced disappearance.(4)

Lethal violence against the press

Violence against journalists is a complex phenomenon. To understand its dynamics and find those responsible, it is not enough to look at organized crime or people who “spontaneously and voluntarily” – as they say in the jargon of the dossiers – confess.

The actors in this lethal scenario plagued by corruption, insecurity and impunity are diverse and varied. There are multiple modalities of violence and patterns of execution. In Mexico, this is particularly pronounced in certain states, such as Veracruz.

According to the UNESCO Observatory,(18) from 1993 to 2023 there is a record of 1642 journalists murdered worldwide. In this period Mexico is the country with the second highest number of murdered journalists (158) after Iraq (201), but the first in the category of countries in the “non-conflict zone”.

According to data from Article 19, in the period 2000-2023, 163 journalists were documented murdered in Mexico, of which 31 correspond to Veracruz -the first state on the list-, followed by Guerrero, Tamaulipas and Oaxaca with 17, 15 and 15 respectively. And if we go into the period we specifically analyzed 2010-2016, more than half were murdered in Veracruz (17). For that reason it was decided to analyze the context of that state. https://articulo19.org/periodistasasesinados/

Why are journalists killed? The answer is not simple. On many occasions the state government explained the crimes by simply saying that the victims “had links with organized crime”. The words of Governor Javier Duarte are well known when, at a press conference in Poza Rica, he told the journalists present: “Behave yourselves, we all know who are in the wrong… We all know who in some way or another has links with these groups […], we all know who has links and who is involved with the underworld […], behave yourselves…«(19).

20 are the victims of the period studied (17 murdered and 3 still missing), all of them journalists who exercised their profession in a difficult context where organized crime imposed rigor and risk, and the State allowed or played a leading role in the annulment of rights, the discrediting of victims, the abuse of power by officials and the omission of truth and justice.

The context was also rarefied by the struggles and social demands generated by various sectors, especially as a result of insecurity and socio-environmental violations caused by hydroelectric projects, as well as the intensification of oil and mining exploitation in Veracruz.

Added to this was the situation of vulnerability and labor precariousness that journalists lived -and still live- with very low salaries, no social security benefits and little support for technical equipment or security, in addition to the editorial commitments of media owners to powerful groups. All of the above hinders or restricts freedom of expression even more, since the economy of journalists and the media depends in part on politics. Unofficially, it is estimated that 60% of the income of the media throughout the country comes from official advertising(20) and this financial dependence sometimes demands a closeness to power which may -or may not- translate into news.(21) Between politics and journalism “a relationship of interests is generated between both parties, some to provide information; and others to be seen, taken into consideration”.(22)

On the other hand, it is not strange to corroborate that some media owners are also politicians. Such is the case of Eduardo Sánchez Macías, according to documents, owner of the editorial group that publishes the “Heraldos” newspapers and at the time a local deputy. There is also Alejandro Montano, former congressman and former Secretary of Security, who at one time held the state concession of Milenio. The above generates perverse dynamics that are reflected in criticism, censorship or even cause the government’s social communication coordination budget to be used -prior agreements with media owners- to carry out campaigns of unrestricted support or, in other cases, defamation and political persecution of certain characters.(23)

Organized crime also has an influence on the editorial policies of the media, not only through self-censorship and strategic publication -information “directed” that is, promoted by criminals-, but also through the distribution of money or benefits.(24)

All this blurs the necessary boundaries between the public and the private, the subjective – private interests – and the objective of the state function, directly affecting the exercise of the journalistic profession.

In this complex context, journalists play a role that holds, on the one hand, a share of power and, on the other, a position of risk: the communicator is a generator of news and can point out or silence subjects and events; disseminate information; or silence and make data invisible. Communication and the journalist are useful for organized crime, they are a tool in the field of tension or war that cartels have among themselves. On occasions, they intend the news to instill fear, to bring a threat closer, to mark the dominance of a group over “the square” – as the disputed territory is colloquially called – or even to be an invitation to negotiate.

Also the political sphere that abuses its function tries to dominate them, sometimes using intimidation and violence, using agents of the public security forces as well as members of organized crime.

In summary: being a journalist in Veracruz is above all an act of resistance. And the profession, one of the most risky and extreme.

Modus, practice and pattern of lethal violence against the press

The study with a macro-criminal approach on the modus operandi of disappearances, executions and the modalities of finding the bodies of journalists shows that lethal violence is perpetrated by a network in which private and public actors, officials and members of organized crime participate.

Each case has its own modality, dynamics, interveners and underlying motives, but behind them there are constants.

What central pattern is perceived in these cases of lethal violence against journalists? The answer is not simple. We gathered information from more than 350 documentary sources (books, copies of case files, reports, journalistic notes, press releases and press conferences from the prosecutor’s office and other authorities), as well as from data collected in the field by the research team through interviews with family members and colleagues of the victims. After interrelating and analyzing the information with a macro approach, it was possible to apprehend elements that are repeated in 65 or even 75% of the cases.

All this provided clues to reconstruct a pattern that is strengthened in some regions and specific times. The cities involved are many, but the five most affected are Boca del Río, Poza Rica, Xalapa, Tierra Blanca and Veracruz.

This is evident in the first biennium of the period studied (2011-2012), a time that coincides with the first years of Governor Javier Duarte, as well as with the arrival, movement and struggle between cartels (especially the Zetas and later, Jalisco Cartel New Generation): 2011 was the most violent time in general and above all, against journalists.

In 2011-2012 there were 11 victims of lethal violence. Noel López Olguín was the first reporter to be kidnapped and murdered since Duarte’s term began; he was missing for nearly three months until his body was found.

It was then that the risk conditions began to change for journalists. A colleague interviewed said “in Noel’s time I did not measure the risk of publishing, because before with Fidel Herrera, it was different. And with Duarte everything was screwed up. With the entry of the Zetas and the Secretary of Public Security, Zurita… working with organized crime is difficult, but with the officials it is worse: you don’t know how and how far they will go.»(25)

The first biennium, and even the case of Gregorio Jimenez, is plagued by murder cases that appear to be the work of hired killers or organized criminal groups. Many cases are skewed by the dismemberment and/or decapitation of the victims (7 of 17); the bodies of some people were placed in black bags and left in visible places.

These were followed by two years of apparent tranquility(26) as in 2013 and 2014 there were 2 victims: Sergio Landa Rosado was disappeared and Gregorio Jimenez de la Cruz was killed in February 2014. It is worth noting that the case of Gregorio – who was kidnapped in a commando-style group assault, disappeared and then executed in a very violent manner – was a key case that occurred 18 months after the last homicide, that is, that of Baez Chino, in June 2012.

From then on, the wave of lethal violence resumed. In July 2014, the body of a journalist from Veracruz was found in Oaxaca: Octavio Rojas Hernandez. During 2015, Armando Saldaña Morales, Juan Mendoza Delgado, Moisés Sánchez Cerezo and Rubén Espinosa Becerril were victimized, the latter in the context of a multiple homicide in Mexico City. While in 2016 they murdered Anabel Flores Salazar, Manuel Torres Gonzalez and Pedro Tamayo Rosas, all three in a scandalous, almost public and brazen manner, as happens when impunity is rife. One of the victims was found half-naked, handcuffed and with her head covered with a plastic bag. With traces of torture. The official causes of death were “mechanical asphyxiation by suffocation” and chest contusion from blows, according to press reports.(27) Another was killed by a gunshot to the head near a transit office.(28)

The case of Pedro Tamayo is significant: he was murdered by an armed commando at the door of his home and in front of his family. A relative of the communicator declared that shortly before a “patrol car crossed the avenue, blocking the passage of other vehicles, and facilitating the access of the compact car used by the aggressors who came to attack Pedro”. He also affirmed that the individuals left “calmly, they did not run, they did not seem to be in a hurry, nor alarmed, they took their car” and, after an exchange of high beams with the patrol car, “they left calmly”. When the family asked them to detain the aggressors, the officers “laughed”. The heartbreaking scene continued when the agents “hindered” the arrival of the ambulance by “giving the wrong address on two occasions.”(29) This was the last murder of Duarte’s six-year term. From that moment on, the collapse that had been seen in the political structure was strengthened.

In June 2016, the portal Animal Político published the report “Las empresas fantasmas de Veracruz” (Veracruz’s ghost companies), which denounced a network of 21 companies used by Duarte and some of his top officials to embezzle funds. This is the first of several reports that will be published in the following months in different media. It begins a scandal that will end in the debacle of the governor.(30) In August of that year Arturo Bermúdez Zurita resigns as secretary of public security of Veracruz after a newspaper report in Reforma revealed that he owned 24 companies and that he and his wife had acquired 19 properties, including 5 residences in the United States, worth 2.4 million dollars since he was a Veracruz official. Duarte said he “had no knowledge” that Bermúdez Zurita owned those properties. That same month, they find the grave in Colinas de Santa Fe.(31)

The collapse does not end here, on October 12 Javier Duarte asks for a leave of absence – Flavino Ríos Alvarado (PRI) takes over on an interim basis –(32) and on the 15th he goes on the run. Thus ends Veracruz 2016.

Context of macro-criminality. Public actors and perpetrators

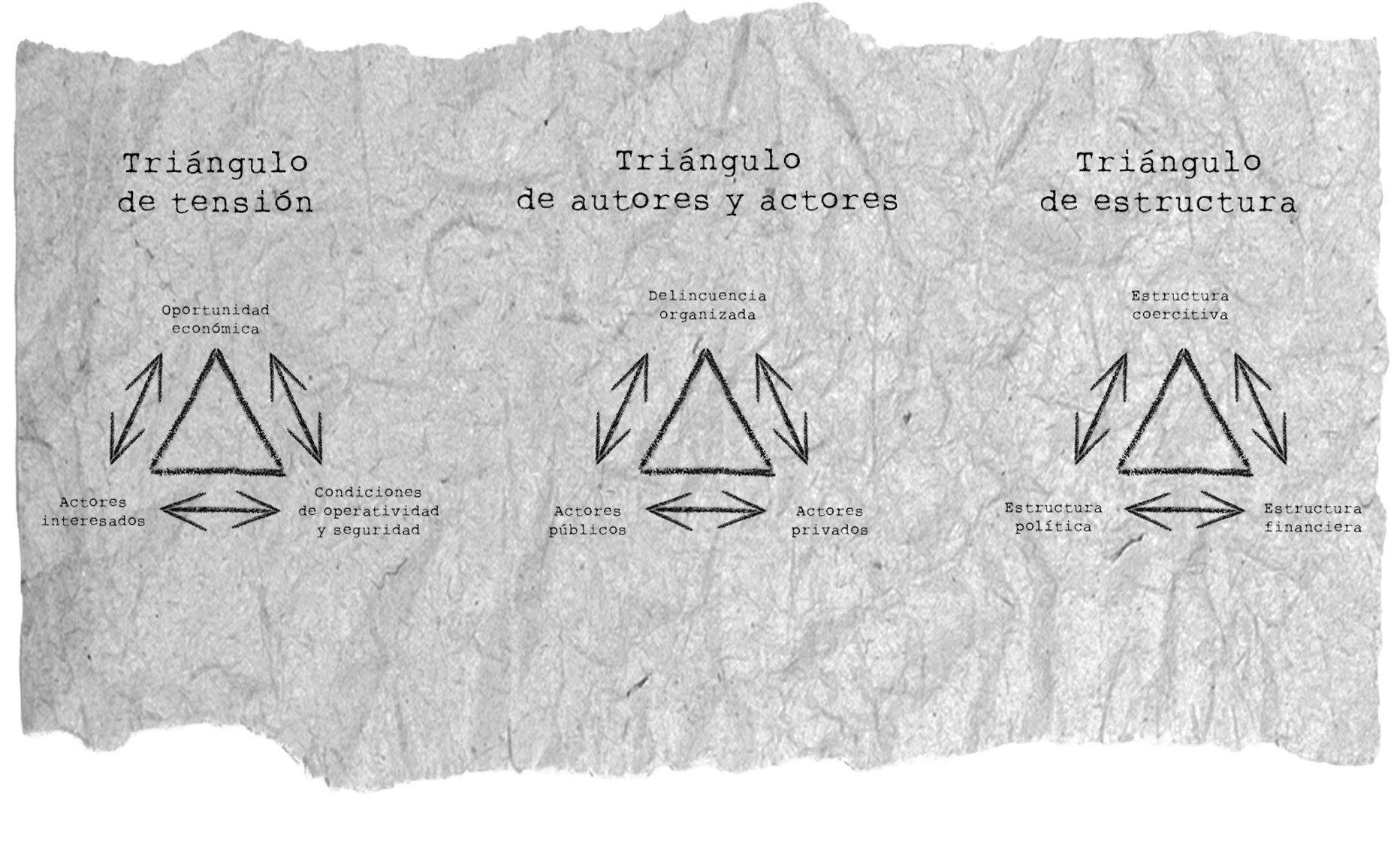

From our perspective,(33) in macrocriminality contexts there are several triangles.

Source: own elaboration.

First, the triangle of tension between economic opportunity, interested actors (licit and illicit) and minimum operating and security conditions (which, depending on the interested parties, could in turn consist of licit or illicit actions, even to the point of demanding guarantees of impunity).

Then there is the triangle of actors and perpetrators. Here, unlike in classical models of criminality, the “phenomena involve an interaction between the public and the private; natural and legal persons, private actors and state agents. This is because macrocriminality operates – and in turn is sustained – in the communion of three basic spheres: 1) the criminal sphere (composed of individuals, legal entities or organized crime), 2) the economic and/or business sphere (individuals or legal entities with private interests), and 3) the political and/or public sphere (congressmen, municipal police, immigration authorities, ministerial agents, judges, among others)”. (34) In other words, in macro-criminality, “(t)he collusion between organized crime, the State and business enterprises makes the actions of these complex illicit networks more than ‘organized crime.’(35)

Finally, there is the triangle of structures, since there must be a coercive vertex, i.e. a set of natural and legal persons, public or private, operating with coerciveness (violent or apparently legal) in order to enforce their own and necessary rules. It is also indispensable to have an operative political vertex, and finally, an economic and financial vertex that gives support and sustenance to what is necessary.

In the lethal violence against journalism, each of these components of the macro phenomena are configured. In Veracruz 2010-2016 three actors interact: organized crime, agents or public officials and individuals or legal entities in the private sphere (companies).

The first major actor is the cartels. This actor often becomes the perpetrator. In the prosecution’s actions, the organized groups or their members are usually pointed out as the alleged (material) perpetrators, and according to the authority and what the confessed persons themselves express, they belonged mostly to the Zetas and CJNG.

There are also charges and names that are repeated in the accusations; officials from the governor’s office, the municipality (mayor’s office) or the police, who contribute, intervene and in some cases not only threaten but are accused of requesting third parties to carry out acts of violence against the press. Thus, Attorney General Luis Ángel Bravo Contreras in a press conference stated that those arrested for the death of Moisés Sánchez indicated that “the death of Moisés was carried out at the direct request of the driver of the mayor of Medellín, in exchange for police protection so that his gang could carry out drug trafficking in that municipality without causing any problems in the municipality…”(36)

On the other hand, according to written sources, Noel López Olguín had death threats against him by the former mayor of Jáltipan. They also say that the federal deputy, Miguel Ángel Morales Cortés, had also threatened him after he published a column against him. The reporter’s colleagues say that once, Noel López met Morales Cortés face to face and without further ado, the local deputy told him: “Fucking dog, here I am going to kill you” and showed him the machete he was carrying in his hand.(37)

And the lethal networks were strong. The case of Rubén Espinosa exemplifies very well the scope of the same. As timely documented by Artículo 19, the journalist left Veracruz and took refuge in Mexico City, because in the last few years he had found it difficult to cover local government events and had suffered threats and intimidation.(38) Therefore, in the face of the aggressions and the daily context of violence against the press, the photojournalist left Veracruz because he feared for his life. Unfortunately, this did not prevent him from being murdered.

Undoubtedly Duarte was an important actor, but he was not the only one; in this phenomenon of lethal violence there are other nodes of interaction such as Gina Dominguez, spokesperson and former head of Social Communication of Duarte’s government. Bermúdez Zurita, former Secretary of Public Security, as well as José Nabor Nava Holguin. Also Felipe Amadeo Espinosa, Reynaldo Gaudencio Escobar, and Luis Angel Bravo Contreras (former prosecutors), Flavino Rios Alvarado, former secretary of Javier Duarte, as well as the aforementioned former mayors.

Private actors and authors

The actors were not isolated. There was an interrelationship between organized crime, public agents and private actors, mainly through pressure and coercion(39) from the former. The media were no stranger to this, as they were another key actor (but not the perpetrator) in the phenomenon of lethal violence.

In Veracruz, each media had the presumed purpose of communicating, sharing news, bringing notes and all in a rarefied context where the danger was daily and the tension increased in direct proportion to the power of the character and/or the topic being reported or investigated. But the media had conditioning factors.

On the one hand, “…organized crime has a growing incidence in the editorial policies of the news media, not only through the ostensible means of self-censorship and the strategic publication of certain types of ‘targeted’ information, but also through the distribution of money, both to businessmen and journalists of all levels, using emissaries from their own ranks or politicians, officials, businessmen or even journalists”(40).

On the other hand, the allocation for official advertising and finally, the agreements. These are sums in the millions. There are several processes in which information on this matter is made transparent, some of them against the former spokesperson Gina Dominguez Colio and other former treasurers and former finance secretaries. There, the prosecutor Julio Rodriguez Hernandez said that it was about 5 billion Mexican pesos,(41) which is equivalent to about 294 million dollars. It is pointed out that the companies did not sign contracts for this, but rather the contribution was given after verbal agreements.

According to others, the amount was higher. An open source detailed what Miguel Ángel Yuñes stated “in 70 months, Javier Duarte’s government paid ”…. two thousand 582 million pesos to newspapers, 152 million to magazines, 15 million to cartoonists, two thousand 700 million to television stations, 515 million to individuals (sic) and 280 million pesos in billboards“(42) In general terms, ‘The unfinished government of Javier Duarte de Ochoa -who has already completed 70 days on the run from justice- spent eight thousand 548 million pesos in the press, advertising, ’purchase” of media and image, assured the Veracruz President Miguel Ángel Yunes Linares”. (43)

The agreements were a major conditioning factor. Organized crime intervened in them. This clouded the work environment. A journalist, when talking about Rubén Espinosa’s work, commented on the situation: “(Rubén) wanted to transmit what was happening and that many times in the media they tried to hide, because there was an agreement or because they had to take care of the editorial line, so he may have been different than the other photographers, but at the end of the day he wanted to transmit what in some companies could not, because we had to take care of the agreement that was ours, where our salary came from (…)”(44).

Finally, we will refer to private investments in the energy sector and the “war against drug trafficking”. In Veracruz, during the governments of

Herrera and Duarte, large private investments were made in the energy field, mainly as a result of the legislative reform given in 2013. And simultaneously “…during both governments, crime and violence overtook the state, causing 332 clandestine graves to be located in 46 of the 212 municipalities, according to public information from the Veracruz State Attorney General’s Office (FGEV). Several of the 46 municipalities mentioned were home to important investments in the energy sector or infrastructure in highways, ports and gas pipelines, among others (…) But the climate of violence to combat crime did not inhibit investments. On the contrary, (…) of the 661 clandestine graves located by Empower in the period 2000-20, 61.57% (407) are concentrated in 57 municipalities where projects to extract oil and natural gas are being carried out or where infrastructure such as roads, ports and gas pipelines are being built (…)»(45) . In other words, there is a clear geographic overlapping and surely of infrastructure or scheme of illegality or co-optation of legality. There is also an abuse of the economic opportunity that the context brings.

Thus, from 2006-2012 the budget for public security quadrupled and the resources allocated to national defense were doubled to finance the so-called “war on drugs”(46) and this had an impact on Javier Duarte’s Veracruz, because adhering to the national security strategy also allowed him access to greater resources. The management of these resources was marked by numerous irregularities, among them, in 2017 the Órgano de Fiscalización Superior del Estado de Veracruz (ORFIS) conducted an audit of the SSP-Veracruz contracting processes of 2016 locating a probable patrimonial damage to the Public Treasury of the state government for more than 214.5 million MXN,(47) found 24 suppliers (companies and individuals) of fuel that did not have evidence to prove the delivery of their services. Regarding these contracts, Empower found in its analysis that four of the five suppliers of the SSP-Veracruz that received 10 contracts for more than 106.7 million MXN were reported by the SAT for performing simulated (ghost) operations: Roberto Esquivel Hernández, Gloria Rodríguez Alcocer, Jesús Murillo Solis and Abastecedora y Comercializadora de Productos de Veracruz, S.A. de C.V. As well as two other suppliers who were benefited with three irregular contracts for more than 33.2 million MXN. These cases are those of Porfirio Aspiazu Fabián, a relative of Major José Nabor Nava Holguín (who became Arturo Bermúdez Zurita’s successor when the latter left the SSP-Veracruz after being accused of illicit enrichment and other crimes). In total, 13 contracts equivalent to more than MXN 140 million assigned to six irregular suppliers were located.(48)

Many of the SSP-Veracruz high commanders who participated in these economic crimes were also actors and perpetrators, that is, they were accused of committing forced disappearances, extrajudicial executions, torture, sexual abuses and other serious human rights violations.(49) Once again, the interrelation between resources and violence is evident. In turn, the case gives rise to reiterate the presence of another of the triangles of macrocriminality and one of its central elements: coercive force.

As noted above, one of the key triangles is that of structures (operational, political and financial). Namely, actors are attracted by economic opportunity (licit or illicit) but need a structure to sustain themselves. In other words, the interested parties (public and private actors) are attracted by the riches of the area such as minerals and hydrocarbons, by the illegal routes, by the flow of public resources destined to the region. And every time the work, investigations and publications of the press touch or harm interests or lucrative advantages (for private individuals or officials) derived from state subsidies, public resources, mining and hydrocarbon exploitation, or the illicit activities generated as a result of the latter (corruption and “huachicoleo”), the risk against the journalist and the press materializes. This happened in Veracruz. It began with conditioning, repression, intimidation and threats, but in many cases ended in disappearances and murders, which, in only six years, totaled two dozen victims.

In these contexts, as the situations are as attractive as they are profitable, the interested actors tend to demand or manage the minimum conditions of operation and security. When they are from the private sector (individuals and companies), they usually request or contract the arrangements. When they are civil servants and politicians, they can act themselves. The problem arises when operability and security are managed at any cost and abandoning legality, i.e. hiring hired assassins, involving organized crime cartels, asking for support from co-opted sectors of the municipal police, among others. All in order to be able to carry out the agreement, enterprise or illegal activity. This is a key vertex within the triangle of structures: the coercive one. In order to materialize the phenomenon, not only financing and political actors are required, but also a binding force that enforces the rules of the illicit system. And one of those rules is to silence those who try to expose or make public the criminal business.

This can be seen in the pattern of lethal violence against the press in Veracruz 2010-2016: disappearances, executions, dismemberments, decapitations, exposure of corpses on public roads, messages on posters on the bodies, all acts of communication to intimidate some and silence others. A clear structure of coercion that has material actors – hired killers, members of organized crime and sometimes public security agents – but also intellectual authors who pay, generate or maliciously cover up this violence (among them, municipal police, mayors, directors, businessmen, as detailed during the context analysis).

The lethal aggression against the press is an attack on freedom of opinion, but also an attack on the right to information. It violates the right of the victims (journalists) to express and disseminate their ideas, opinions, data and research, but also the rights of individuals and societies to seek and receive information of any kind.(50)

The lethal aggression against the press in turn generates a chilling effect that paralyzes not only their peers, but also anyone who knows how to read the message it expresses: whoever opposes the illegal structure, death awaits.

In Veracruz 2010-2016 this aggression fell on journalists, most of them empirical, who worked in adverse economic conditions, which forced them to have more than one activity to make a living. Communicators with precarious work infrastructures, not always supported or protected by the companies that hired them; journalists who had to cover red notes and who were forced to interact in a context of insecurity, where powerful actors such as cartels had weight and power. Organized crime called, controlled and tried to direct media publications, using different strategies.

During that period, Los Zetas had a strong presence, but also others such as the Jalisco Cartel – New Generation and the Sinaloa Cartel. All of them were in conflict with each other and fought by the strategies of the “fight against drug trafficking”. In that context they reported, investigated and published the victims. And that generates risks.

But the main risk comes from the role they played. Today’s journalists, in contexts such as Veracruz, are not only in danger for the story they publish; they are not only at risk for working in an uncertain terrain in which they are constantly walking on the edge without knowing or being able to foresee if their story, report or analysis is going to irritate organized crime or any other illegal power actor (be it an official or a private individual).

The press today plays another role: it is the one who with its work can “heat up or cool down a plaza” -an expression used in criminal jargon to refer to making the scenario or context more chaotic and violent-. It can make a criminal group look powerful and dominant in a region, or depressed and overpowered. It can transmit a message from one side to the other, or to the authority or society. This role makes the journalist a key factor.

Today, war is no longer fought exclusively in the field, in the field, hand to hand. Today the “war” has a more ethereal, digital platform: social networks and/or mass media. It is there where the fights take place, where many contests are defined, where actors (politicians, officials and others) also compete.

So, in this scenario, mastering the profession that works in this combat platform and is in charge of giving or sharing the message is key. In other words: communication and communicators are today an element of this war.

And for this reason, it is necessary to control it. Everything is done to try to instrumentalize it: first we try to bribe, intimidate, condition the press, and if we cannot, we will try to silence it by means of violence. Especially when the message or communication does not add up to the interests of certain actors (corrupt officials and companies, individuals or criminal enterprises, and also cartels).

This is the new risk for journalists. It is not a punctual note. It is not the danger of working walking on the ledge. This can happen, of course, since these are the first circles of danger for this actor. But at present, the journalist’s risk is the role assigned to him/her in the current dispute scenario: a communication tool that the actors (participants) of this war intend to instrumentalize.

This was perceived when analyzing the context of Veracruz and above all, the motives approached for the pattern.

The necessary infiltration of illicit powers in state structures was also observed. On the one hand, organized crime attempts to co-opt public security agents or agencies or executive branch bodies. On the other hand, it can be seen how public and private actors (officials, employees, businessmen) abandon the sphere of legality and become illicit powers that work or manage from social or state institutions, protected by the cover-up of others and/or aided by mechanisms of impunity.

As can be seen, the phenomenon of lethal violence is not two-dimensional (aggressor-victim) but plural and multidimensional. They are complex networks of corruption and crime, in which various actors interact dynamically. It is from this macro-criminal perspective that we must analyze the phenomenon. Prosecutorial investigations must be approached with this focus. Only in this way will there be “due diligence”.

The Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression established by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (RELE-IACHR) said: “The State is obliged to identify the special risk and warn the journalist of its existence, assess the characteristics and origin of the risk, define and adopt specific protection measures in a timely manner, periodically evaluate the evolution of the risk, respond effectively to signs of its realization and act to mitigate its effects. The State must pay special attention to the situation of those journalists who, due to the type of activities they carry out, are exposed to risks of extraordinary intensity»(51).

The efforts of the Mexican State have been many. In 15 out of 20 cases there are accused or detained, but almost all of them are direct actors (material authors) with questionable real implication in the facts, given the lack of credibility of some procedures and procedural acts. The intellectual authors have not been identified. There is a lack of study of the structures of operation of these illicit acts. There is a lack of firm convictions. The victim does not have real access to the files. Above all, there is a lack of a comprehensive, systemic and macro-criminal approach to lethal violence against the press in the investigations, because the phenomenon shows in practice to have these characteristics.

Notes, quotes.

(1) Andrés Ruiz Pérez, “Veracruz tuvo 80 años de gobierno PRI, desde 1936-2016”, 2008. Pág. 15-25

(2)Atlas de indicadores de la ONU 2000-2010. https://www.uv.mx/cuo/files/2013/11/ATLAS-DE-INDICADORES-ONU-2000-2010.pdf, p.108-109 . En los resultados de la Tabla 13 se aprecia que en el año 2009, la Zona Metropolitana de Poza Rica (con 3.25 Homicidios por cada 10,000 habitantes), presenta la tasa de homicidios más alta de las 8 ZM del Estado, seguida de la ZM de Veracruz y la de Córdoba (con tasas de 2.92 y 2.73 respectivamente). En contraste la ZM de Xalapa (1.77 homicidios) y la ZM de Orizaba (con una tasa de 2.07 homicidios) son las que presentan una menor tasas de homicidios por cada 10,000 habitantes.

(3)Nación 321, “El día que Calderón declaró la guerra contra el narcotrafico”, https://www.nacion321.com/politica-1/el-dia-que-calderon-declaro-la-guerra-contra-el-narcotrafico1; Reuter, “Datos-principales hechos de la guerra antinarcotrafico en México”, https://www.reuters.com/article/latinoamerica-delito-mexico-operativos-idLTASIE6AS0YH20101129. https://www.washingtonpost.com/es/post-opinion/2019/10/28/aos-y-muertos-las-lecciones-no-aprendidas-en-mexico.

(4)Ver Empower, “Corrupción a gran escala en la secretaría de seguridad pública de veracruz: elementos económicos para entender graves violaciones a derechos humanos”, 2022. Pag. 10. https://crimenesgraves.empowerllc.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/2.-Corrupcion-a-Gran-Escala-en-la-Secretaria-de-seguridad-pública-de-veracruz.pdf

(5)Víctor Manuel Andrade Guevara, “Violencia y régimen político en Veracruz, México: 1936-2016”. 2018. https://www.redalyc.org/journal/855/85559555004/html/

(7)La Organización Mundial de la Salud considera que una tasa de homicidios superior a 10 por 100.000 habitantes es una epidemia” https://www.undp.org/es/latin-america/blog/una-epidemia-en-movimiento-el-cambiante-panorama-de-la-seguridad-ciudadana-en-america-latina-y-el-caribe#:~:text=%5B1%5D%20La%20OMS%20clasifica%20una,100.000%20habitantes%20como%20“. Tambien https://www.sica.int/download/?-834, entre otros. La expresión epidemia” ofrece resistencia y genera discusiones. https://factual.afp.com/no-ni-la-oms-ni-la-onu-utilizan-la-expresion-epidemia-de-homicidios

(8)Comunicado de prensa N.376/22 INEGI 2022 con base en datos relevados en 2021: https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/saladeprensa/boletines/2022/DH/DH2021.pdf

(9)Ver: https://www.reuters.com/article/latinoamerica-delito-México-veracruz-idLTASIE7A7ILG20111007 https://expansion.mx/nacional/2011/10/06/la-marina-localiza-32-cuerpos-en-casas-de-seguridad-en-veracruz

(10)El portavoz de la Secretaría de Marina (SEMAR) José Luis Vergara señaló que CJNG «se trata de otro grupo del crimen organizado antagónico a la organización delictiva de Los Zetas, cártel con el que se disputa el control de actividades y recursos ilegales de Veracruz para la comisión de delitos». El cártel Jalisco Nueva Generación surgió a raíz de las divisiones en la estructura del tráfico de drogas tras la muerte en 2010 de Ignacio Coronel, alias «Nacho Coronel», uno de los líderes del poderoso cártel de Sinaloa. Cfr. https://www.diariocordoba.com/internacional/2011/10/07/detenidos-20-sicarios-veracruz-incluidos-37710475.html

(11)En septiembre de 2011, el portal web denominado Blog del Narco, presentó un video, en donde se conoce un narcocomunicado del grupo que se autodenomina Los Mata-Zetas https://www.metatube.com/en/videos/76039/Narcocomunicado-de-Los-Mata-Zetas/

(13)Jesús Espinal Enriquez, Ernesto Isunza, Andrea Isunza, Daniel Vazquez, “Redes de macrocriminalidad y violencia: Dinámicas regionales en Veracruz: 2004-2018”. 2023. Pág. 20-22. https://archivos.juridicas.unam.mx/www/bjv/libros/15/7198/16.pdf

(14)Víctor Manuel Andrade Guevara, “Violencia y régimen político en Veracruz, México: 1936-2016”. 2018. https://www.redalyc.org/journal/855/85559555004/html/

(15)Empower, “Corrupción a gran escala en la secretaría de seguridad pública de veracruz: elementos económicos para entender graves violaciones a derechos humanos”, 2022. https://crimenesgraves.empowerllc.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/2.-Corrupcion-a-Gran-Escala-en-la-Secretaria-de-seguridad-pública-de-veracruz.pdf

(16)Empower, “Corrupción a gran escala en la secretaría de seguridad pública de veracruz: elementos económicos para entender graves violaciones a derechos humanos”, 2022. https://crimenesgraves.empowerllc.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/2.-Corrupcion-a-Gran-Escala-en-la-Secretaria-de-seguridad-pública-de-veracruz.pdf

(17)Víctor Manuel Andrade Guevara, “Violencia y régimen político en Veracruz, México: 1936-2016”. 2018. https://www.redalyc.org/journal/855/85559555004/html/

(18)UNESCO. Observatory of Killed Journalists. Disponible en: https://www.unesco.org/en/safety-journalists/observatory/statistics

(19)La Jornada. disponible en: https://www.jornada.com.mx/2016/03/08/opinion/017a1pol

(20)Celia del Palacio, Alberto J. Olvera. “Acallar las voces, ocultar la verdad violencia contra los periodistas en Veracruz» .2018. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/595/59555067006.pdf

(21)Rubén Arnoldo González Macías, Dulce Alexandra Cepeda Robledo. “Trabajar por amor al arte: precariedad laboral como forma de violencia contra los periodistas en México”. 2021. https://gmjmexico.uanl.mx/index.php/GMJ_EI/article/view/434/464

(22)Felipe Bustos González, “Violencia contra periodistas en Veracruz: una pugna por la notoriedad pública, 2004-2016”. 2019. http://148.226.24.32:8080/bitstream/handle/1944/52264/BustosGonzalezFelipe.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

(23)“Informe de agresiones a periodistas para la Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos en su visita in loco a Veracruz”. 2015. https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/INFORME_VERACRUZ_PLATAFORMAPERIODISTAS.pdf

(24)Marco Lara Klahr, “Y 30 años después… Medios noticiosos, periodistas y crimen organizado en México”. 2014https://nuso.org/articulo/y-30-anos-despues-medios-noticiosos-periodistas-y-crimen-organizado-en-mexico/

(25)Según datos proporcionados por el entrevistado número 23

(26) Son varios los eventos violentos no letales durante el período. Entre ellos, la protesta del 14 de septiembre de 2013, manifestación de profesores tras la cual varios periodistas fueron golpeados, detenidos, encarcelados e interrogados por la policía estatal, que les quitó su equipo: Animal Político. “Desaloja policía a maestros en Xalapa”. 14/09/2013. Disponible en: https://www.animalpolitico.com/2013/09/desaloja-policia-a-maestros-en-xalapa

(27)Matar a Nadie. Disponible en: https://mataranadie.com/anabel-flores-salazar/https://www.lapoliticaonline.com/mexico/en-foco-mx/n-88477-periodista-veracruzana-asesinada/

(28)Entrelíneas. “DE UN TIRO EN LA CABEZA FUE ASESINADO EL PERIODISTA MANUEL TORRES GONZÁLEZ”. 15/05/2016. Disponible en: https://entrelineas.com.mx/mexico/de-un-tiro-en-la-cabeza-fue-asesinado-el-periodista-manuel-torres-gonzalez/; Imagen del Golfo. “Ejecutan a ex reportero de Tv Azteca en Poza Rica; van 18 asesinados en Veracruz durante el actual gobierno”. 14/05/2016. Disponible en: https://imagendelgolfo.mx/policiaca/ejecutan-a-ex-reportero-de-tv-azteca-en-poza-rica-van-18-asesinados-en-veracruz-durante-el-actual-gobierno/352154

(29)Univision. “Familiares del periodista asesinado Pedro Tamayo aseguran que la policía fue cómplice de los criminales”. 22/07/2016. Disponible en: https://www.univision.com/noticias/asesinatos/familiares-del-periodista-asesinado-pedro-tamayo-aseguran-que-la-policia-fue-complice-de-los-criminales

(31)https://www.forbes.com.mx/descubren-en-veracruz-la-fosa-mas-grande-de-america-latina/ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qobJdo9NQGg

(33)Quintero, María Eloísa, “Persona jurídica y crimen organizado; reflexión sobre migración ilegal y trata de personas”, en Ontiveros Alonso, Miguel (coord.), Responsabilidad de las personas jurídicas, México, Tirant lo Blanch, 2014, pp. 571-598. Tambien Quintero, María Eloísa, Compliance en caso de trata de personas, tesis doctoral presentada en la Facultad de Derecho de la Universidad Austral para obtener el título de doctora en derecho, pp. 12-24 y 49 y ss., disponible en: https://riu.austral.edu.ar/bitstream/handle/123456789/660/QUINTERO%2C%20Ma.%20ELOISA%20-%20Tesis.pdf ?sequence=1; id., “Migración, trata y tráfico. Acciones regionales: la experiencia del Mercosur”, Homenaje a sus 100 años de la Escuela Libre de Derecho, México, Escuela Libre de Derecho, 2014, pp. 1-40.

(34)Quintero Maria Eloisa, “Macrocriminalidad y corrupción. Cinco herramientas de combate e investigación”, en» La justicia penal en México «, Sergio Garcia Ramirez y Olga Islas de Gonzalez Mariscal coord. https://biblio.juridicas.unam.mx/bjv, p. 341

(35)Eduardo Salcedo-Albarán Y Luis J. Garay-Salamanca “Macrocriminalidad. Complejidad y Resiliencia de las Redes Criminales”. 2016. Disponible en: https://www.cels.org.ar/web/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Macro-criminalidad.pdf, p.27

(36)LA GAZETA TV. 27/01/2015. min.1:59 en adelante. Disponible en: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p63cr8qfOzg

(37)https://www.ladobe.com.mx/2014/02/desaparecio-rumbo-a-soteapan/

(38)El miércoles 10 de junio 2015, por la mañana, el fotoperiodista notó a una persona afuera de su casa, en Xalapa. “No le di mucha importancia y seguí camino a realizar mi trabajo”, relató Espinosa en entrevista con ARTICLE 19. En la tarde, dos individuos más permanecían frente a su hogar. “Tres me veían de manera agresiva, ahí se encontraba el primer sujeto, quien aparentemente me tomó una foto y me hizo una seña como de ‘¿Qué pedo?’”. En la noche, cuando regresaba a su casa, dos personas lo siguieron, por lo que se refugió en una tienda de artículos para bebé. Minutos después, el fotoperiodista continuó su camino. Antes de llegar observó que afuera de su casa otras dos personas lo esperaban. Cuando lo vieron caminaron hacia él y Espinosa se hizo a un lado para dejarlos pasar. Éstas se detuvieron, lo miraron fijamente y se fueron.

Un día antes, el comunicador encabezó el acto de la recolocación de una placa en honor a la periodista Regina Martínez, asesinada en la misma entidad el 28 de abril de 2012.

(39)En una ocasión supuestos narcotraficantes depositaron en la puerta principal de Notiver la cabeza de un zeta ejecutado un día antes acompañada del mensaje «aquí te dejamos un regalo… así van a rodar muchas cabezas, Milovela lo sabe y muchos más, van cien cabezas por mi papá. Atentamente, el hijo de Mario Sánchez y la Gente Nueva” -haciendo referencia a CJNG- . Según blog.expediente y en el mismo sentido lo comenta la entrevistada número 11.

(40)Marco Lara Klahr. «Y 30 años después… Medios noticiosos, periodistas y crimen organizado en México». 2014. Disponible en: https://nuso.org/articulo/y-30-anos-despues-medios-noticiosos-periodistas-y-crimen-organizado-en-mexico/

(41)https://www.debate.com.mx/politica/Gina-Dominguez-es-vinculada-a-proceso-20170527-0047.html

(42)Proceso, “Gobierno de Duarte gastó más de 8 mmdp en prensa: Yunes Linares” 28/12/2016. Disponible en: https://www.proceso.com.mx/nacional/estados/2016/12/28/gobierno-de-duarte-gasto-mas-de-mmdp-en-prensa-yunes-linares-176156.html

(43)Plumas libres. “Duarte gastó 8 mil mdp en medios de comunicación: MAYL”. 29/12/2016. Disponible en: https://plumaslibres.com.mx/2016/12/29/duarte-gasto-8-mil-mdp-medios-comunicacion-mayl/

(44)Según datos proporcionados por el entrevistado número 3.

(45)Empower lcc.; «Fosas clandestinas y desaparición forzada»; 2022. Disponible en: https://crimenesgraves.empowerllc.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/1.-Crimenes-Graves-en-Veracruz-Fosas-clandestinas-y-desaparicion-forzada.pdf

(46)Empower. «Corrupción a gran escala en la Secretaría de Seguridad Pública de Veracruz». 2022. Disponible en: https://crimenesgraves.empowerllc.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/2.-Corrupcion-a-Gran-Escala-en-la-Secretaria-de-seguridad-publica-de-veracruz.pdf

(47)“Informe del Resultado de la Fiscalización Superior. Secretaría de Seguridad Pública. Cuenta Pública 2016”, ORFIS, 2017, www.orfis.gob. mx/informe2016/archivos/TOMO%20I/Volumen%202/002%20Secretar%C3%ADa%20de%20Seguridad%20P%C3%BAblica.pdf. Pág. 63.

(48)Empower. «Corrupción a gran escala en la Secretaría de Seguridad Pública de Veracruz». 2022. Disponible en: https://crimenesgraves.empowerllc.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/2.-Corrupcion-a-Gran-Escala-en-la-Secretaria-de-seguridad-publica-de-veracruz.pdf

(49)Empower lcc.; «Fosas clandestinas y desaparición forzada»; 2022. Disponible en: https://crimenesgraves.empowerllc.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/1.-Crimenes-Graves-en-Veracruz-Fosas-clandestinas-y-desaparicion-forzada.pdf

(50)En ese sentido https://www.oas.org/es/cidh/expresion/docs/brochures/violencia-periodistas-largo.pdf

(51)RELE-CIDH- «Actos de violencia contra periodistas» disponible en: https://www.oas.org/es/cidh/expresion/docs/brochures/violencia-periodistas-largo.pdf Pag. 4