México

Why are journalists killed in Mexico?

By Paula Mónaco Felipe

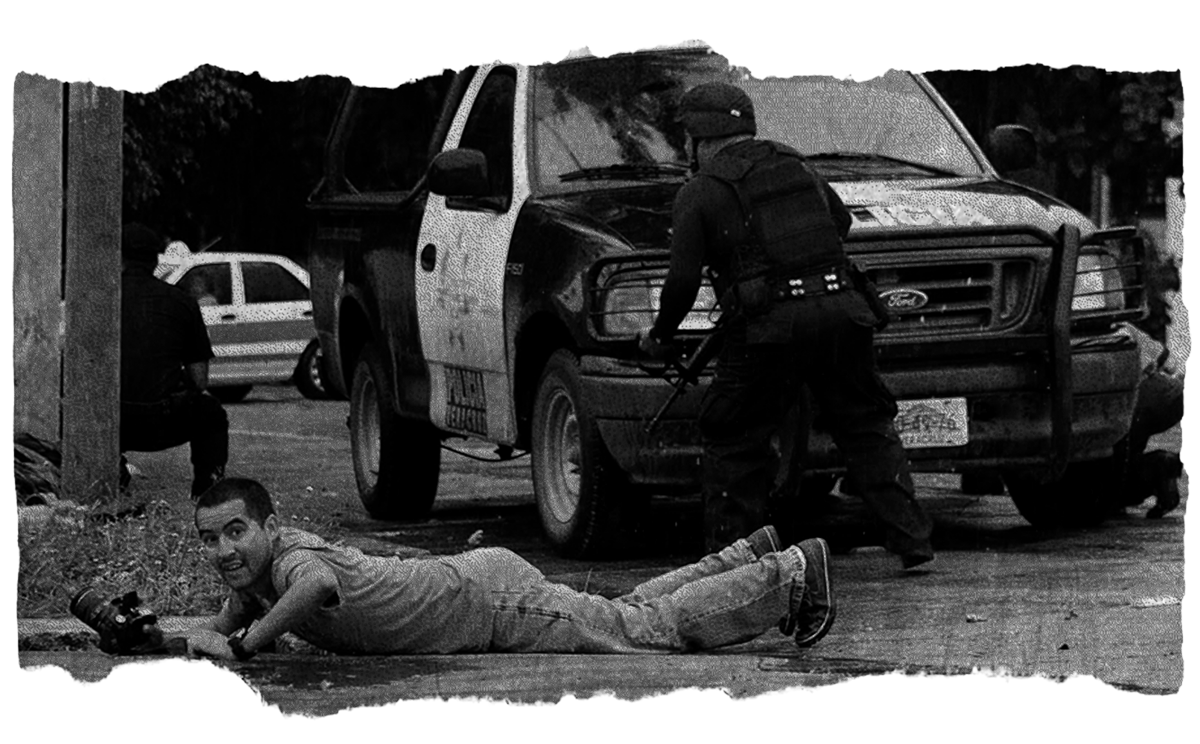

Photos: Miguel Tovar

It has been said that journalists are targeted by drug cartels and government officials who enjoy impunity. But there is no single explanation for the increase in violence against the press over the past 20 years. That is why we decided to analyze the worst period and the worst territory to be a journalist in Mexico: the years 2010-2016 in Veracruz. In a state where at least seventeen journalists have been murdered and three disappeared, we discovered many worrying facts: the population is still afraid, important information is disappearing, many investigations have gone cold, those responsible for the crimes remain free, and many of them are even more powerful. A third key actor has also been identified: media corporations. The private sector is a concentrated, toxic mix of conflict of interest and inequality. This research sheds new light on the who, what, how and why journalists are killed

1. Page editing

It is afternoon rush hour. Rushing to make sure the article is well written, checking to see if the photos are there. Adjust here, cut there. Does the headline work or should it be changed? No newsroom is quiet in the afternoon; everything is a race against the clock.

Dario Cardel’s windows are open because it is hot. Even in winter, the temperature can reach 30 degrees Celsius. It gets worse when the north wind blows: a soporific, headache-inducing wind invades every corner.

«What will you publish tomorrow?» asks a man through the window.

He asks today, as he asked yesterday, and will ask again tomorrow. And it will not be just one man, but many. Sometimes with visible weapons. Other times they do not even need to show their weapons, because everyone knows who they are: gunmen working for the boss of the plaza. They often come to the newspaper to ask what will be in the next day’s edition.

They are not the only ones. Some afternoons, policemen also knock on the door. They come from different departments to check and decide what news will make the headlines, what photo will be shown, or how the news will be reported. They also ask to come inside or wait outside for detailed information. In other cities of Veracruz, and in many others across the country, the press is controlled by telephone. Calls at night to tell reporters what can be published; messages on reporters’ phones to dictate what the news will be.

It is known that for years some major newspapers in Veracruz have sent their front pages to be reviewed by the sitting governors. But in Cardel in 2012, it goes beyond anything imaginable. Drug cartels and police come to review – and sometimes edit – the front page.

José Cardel is a town of 19,000 inhabitants and much more important than this number would suggest. Cardel is where Federal Highway 180, which crosses the country, meets State Highway 40, which connects the port city of Veracruz to the state capital of Xalapa. The train also passes through here. And it is only 30 kilometers from the economic capital, Veracruz-Boca del Río.

José Cardel is very valuable as a commercial center, legal or not. Perhaps that is why it has been held hostage by the cartels. With the arrival of the Matazetas in Veracruz, it was one of the first places to be conquered in order to wrest territorial control from Los Zetas. In the same place where there was once a popular carnival and green fields of sugar cane, death began to rot everything. Murders and dumped bodies. Decapitated, mutilated remains were placed in garbage bags and people disappeared; days became difficult and nights impossible.

From 2007, Cardel went through a very dark period. Organized crime invaded and took over many media outlets and many of the people who worked for them. A journalist who fled Cardel for their safety recalled that it was impossible to even talk – even if you were at home – because the criminals could find out what you were talking about.

No one wanted to talk, but everyone wanted to read. The crime reporting business exploded. Diario Cardel began selling between 3,000 and 3,500 copies a day, which meant that one in six residents bought the paper.

Every morning, the most important news was announced on motorcycles equipped with loudspeakers like those used in cars to make community announcements. And people rushed to buy them. Information about murders always sold newspapers.

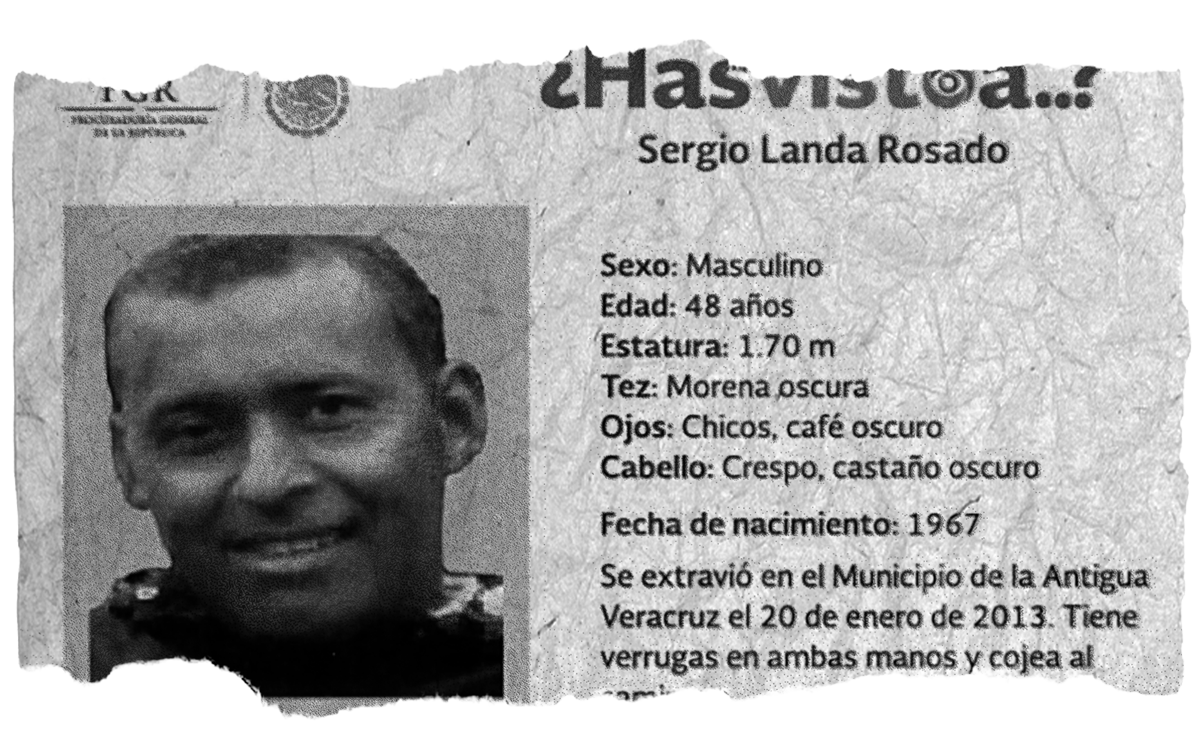

In the photo, he is smiling as he displays his congressional candidate registration. He wears a white polo shirt and a backpack on his left shoulder.

«Foul-mouthed, like all the people of Veracruz. But noble, honest and without malice. This is how Jesús Augusto Olivares Utrera describes his former colleague Sergio Landa.

He says that Landa was always popular and well-liked in his community, which is why the Nueva Alianza political party offered to register him as a candidate for congressman for the 13th district (Huatusco). He never took the position; he withdrew one day before the elections because the political party had not fulfilled its promise to finance the campaign with a car and to give an advertising contract to the newspaper with which he worked. Sergio Landa was born in El Zapotito, a town that has 762 inhabitants today and was even smaller during his childhood. His parents were farmers and he had many brothers and sisters.

He loved to draw and always hoped to be able to study. He started a career in graphic design, but could not finish it due to a lack of funds to pay for his studies. So he became a sign painter, an old trade that consisted of hand-painting letters, logos and advertisements on signs or walls.

Sergio also made belts and was a soccer referee. His friends remember him as a partygoer, dancer and salsa enthusiast. But also an entrepreneur, someone with a big heart and a fearless desire to succeed. Maybe that is why he became a journalist.

He was unemployed when he heard that Diario Cardel was hiring a designer. When he arrived, it turned out that they needed a reporter, and Sergio said yes, even though he had never worked in the media before. For his enthusiastic but haphazard approach, some called him Speedy González, because he would ride his motorcycle at full speed to get to the scene of the crime on time. Others nicknamed him «the rubber journalist» because he often fell off his bike but quickly got back on his feet.

His contacts grew over the months: Landa made connections in the armed forces, emergency services, police departments, and, like almost everyone, people in organized crime, including people in uniform. He talked to them, tried to negotiate the stories. In front of him, they called the «papas» (potatoes), as they called the police, to ask questions, to ask for clarifications, to give orders.

Sergio became an «empirical,» as they call those in Veracruz who did not study journalism but became journalists through hard work. Once inside, he liked the adrenaline rush. He was especially drawn to crime news. Crime reporters say it gets under your skin. If you like covering crime, it is a job you cannot escape – it becomes a kind of addiction.

In those years, journalism in Veracruz was exciting, but not an easy livelihood. As violence increased, the media became big business.

Media entrepreneurs pushed for the most explicit photos and the most revealing information; that made money. Similarly, the cartels forced their agenda on the media: Los Zetas wanted to show their executions to instill terror, and Los Matazetas (later Jalisco Nueva Generación) told journalists not to show blood because they wanted a different image. In this scenario, journalists were caught in the middle.

Pressure came from all sides, and orders were often contradictory. Who should you listen to? How do you refuse when every order is an implicit threat?

To make matters worse, reporting in Veracruz in those years meant risking one’s life for little money. In the beginning, Sergio Landa earned 3,000 pesos a month, or 107 pesos a day. After a few years, he was able to earn up to 5,000 pesos a month, without social security or paid leave. Less than ten dollars a day.

He was kidnapped twice, in 2012 and 2013. The second time he did not return.

2.The agreements.

A mystery: at least 27 media outlets, almost all of them newspapers, were closed in Veracruz around the year 2016.

Some of them are: El Diario del Sur, AZ Veracruz, Milenio El Portal, Marcha, Oye Veracruz and Capital Veracruz. Also, El Diario de Minatitlán, Matutino Expréss, El Mundo de Poza Rica, El Despertar de Veracruz, Veracruz News, La Voz del Sureste, and Mundo de Xalapa, among others. They come from different regions of Veracruz; they all have different histories and owners. But they all stopped publishing at almost the same time, disappearing from one day to the next, as if struck by an evil spell. The mystery deepens: around the same dates, at least five other newspapers stopped their print editions and went digital only. Many have closed or reduced their newsrooms to a minimum.

The crisis facing print media is global; even the New York Times has considered ceasing publication, and other major publications such as El País have suspended editions in some regions. But something else happened in Veracruz at the end of the 2010-2016 administration. The malaise that spread from newsroom to newsroom was the end of the magic potion that sustained everything: government advertising contracts.

These agreements meant that the government of Javier Duarte directly awarded contracts to news outlets to publish content commonly known as «official publicity. These funds were sometimes unlabeled, with unclear objectives, and distributed as blank checks.

Government advertising is necessary because media companies are businesses that need financing, but in Veracruz and many other states, it has been used as a reward for compliance and as an incentive for tailored coverage.

The official agreement or allocation of state resources to the media is not new. Decades ago, former President José López Portillo made it clear: «I don’t pay to be criticized. Nor is the weight of government advertising new. Such vital funding exists throughout the country and, according to independent studies, accounts for nearly 60% of media revenues. In Veracruz, the government of Fidel Herrera is remembered for handing out money, but during the Duarte administration, the situation has reached extraordinary proportions. «Behave well,» Governor Duarte would tell journalists, while a special branch of his government took care of what that message meant.

The Office of Social Communication went from a budget of 50 million pesos in 2011 to 304 million pesos in 2016. It multiplied its budget by 452 percent, according to the 2011 Budget Law and a report prepared by the Comptroller General at the request of local legislators. Outrageously higher figures were later revealed: Duarte’s government paid out nearly 5 billion pesos, or about $294 million, in press contracts, according to statements made by prosecutor Julio Rodríguez Hernández in a pretrial hearing.

The allocation of this budget was decided by only one person: María Gina Domínguez Colio. With short hair, blond highlights, thin eyebrows, and a fierce look, she was one of the most powerful figures in the administration. As a result, she was nicknamed the Vice Governor. In addition to her personality, her professional background stands out: she is a journalist with extensive experience, familiar with every aspect of Veracruz’s media landscape.

«She was in charge of damage control,» says a journalist who requested anonymity. She was in charge of denying news that had already been published. She also called newsrooms and said, «Take down that story; put up this one instead. She identified people and put them in danger. She was so powerful that when they found the 34 bodies in houses in a residential area of Boca del Río [in 2011], Gina denied the news. Then the Navy denied what she had said. But she was not fired.

Another journalist, also speaking on condition of anonymity for security reasons, continues:

«Gina would get reporters fired if they went off script. She controlled the photos and what would and would not be published in all the media. The intimidation was intense. First, the obvious: censorship. If you insisted, she would scold you or get you fired; they would suspend or delay your [government advertising contracts] payments. A perfectly designed system. And if you kept a job despite being fired from all the media, they would continue to intimidate you. They intimidated you, they monitored you, and the last thing they did was to give you «una calentadita» (a form of beating to send a message). No, sorry, the last one was death. Because that was something we witnessed, they started doing that a lot. But I do not know exactly how they worked; it was all rumor.

Domínguez handled mountains of money, perhaps even more than the documents reveal, because at the end of the administration, some outstanding contracts were made public. A detailed list of these debts, with the names of the companies, amounted to at least 400,146,820.86 pesos, while the approved budget for that year was 304 million, according to Plumas Libres. When journalists requested the amounts and details of the payouts to media outlets, the government responded that this was classified information.

The price of silence. Paid mutism. Debts «to media and journalists who have helped to «incense» the current governor, hide shootings and deaths, and report violent events as if they were robberies, when in some cases they were executions. They looked the other way when they knew it was a case of a mother looking for her son, disappeared by the Zetas, by the Jaliscos, or by police patrols,» wrote Ignacio Carvajal in an article published on July 11, 2016. Years later, in 2023, during a book presentation in Mexico City, journalist Norma Trujillo sums up: «In Veracruz, there is no real independent media; government advertising sets the tone.»

Another colleague, who asked not to be identified, talks about this almost without surprise, as if it were normal:

«It’s well known that almost all media outlets reported to Duarte’s social communications office. That was my job when I worked at the newspaper I mentioned earlier; I was in contact with [a particular person] because I was the editor-in-chief and was asked to contact him to know what statement the governor wanted to publish. I always called him. That went on for years.»

The growing power of government contracts during the Duarte era created surreal situations. In 2015, when some journalists protested outstanding payments for official propaganda, two executive directors stood in front of the government palace in Xalapa with signs that read, «There is no longer money handed out (chayote); the government has other priorities.»

According to documents published by Noé Zavaleta in Proceso, the Duarte government paid «between 200 and 230 million pesos for government advertising in radio, press and television (…) And although this money was labeled, it was not always given to the media.

Scandals piled up. Duarte’s flight, along with part of his cabinet, became imminent. Nevertheless, government debts remained. For example, the newspaper Marcha was among those that suddenly disappeared and to which the government owed 4,788,000 Mexican pesos. AZ also disappeared, with an outstanding debt of 27 million pesos.

According to a list published in 2016, there are 127 unpaid government advertising contracts. The list includes legal entities, anonymous variable capital companies, and the names and surnames of individuals. There are publishing houses, communications companies, radio stations, and consulting firms mixed with acronyms that say little about who they are. Most are linked to the state of Veracruz, but they include leading national media such as El Universal ($3,800,000), Excélsior Newspaper ($4,000,000), the NRM Communications Group ($2,970,400.31), and Reporte Índigo ($7,795,200).

This is a list of those who tried to claim debts at the end of the 2010-2016 administration, with no certainty about the total number of claims or the destination of the money that came out of the Veracruz Social Communications Office (Gina Domínguez’s office) during that six-year term. In 2023, more than a decade later, the Office of Contracts and Agreements of the Government of Veracruz responded to freedom of information requests that «the information requested is not available. Either they have nothing to share or they choose not to share.

3.Is it possible to say «no»?

It was one of those routine stories – the ones that don’t matter much. Taxi drivers protesting for more safety. A short article that appeared in the print edition and seemed to get lost among the others. But at eleven in the morning, the editor called.

«Are you alright? There was a problem with the story you published.»

«But it’s informative!»

«You know you’re not supposed to publish things like that.»

His stomach was in knots, his heart was racing, and a shiver ran down his spine. Journalists in Veracruz know how much danger lurks behind the phrase «there was a problem with your story»: it means your life is in danger.

The phone rang again. It was the cartel calling him, telling him to go to a certain place. These calls cannot be ignored. You are obligated to keep those appointments, even if you know you may not come back.

He went to the designated place.They drove by in a medium-sized white car and told him to get in. Inside the car were young men with shaved heads and many tattoos.

A large AR-15 rifle was clearly visible.

«We report what happens. Our editors-in-chief decide what to publish and what not to publish,» he tried to explain, trying to excuse himself.

«Your boss already knows what to publish and what not to publish. Don’t you know that we pay your boss? Doesn’t he give you anything?» the zone boss replied with a certain astonishment. «Here is my number. Next time, call me.»

The terror of non-negotiable calls and appointments. The certainty that the chief of the zone had paid the director and that he had accepted the money, conditioning the journalists without telling them which side to play for. And that he did not distribute the money.

The payments in the newspaper were forty pesos, or two dollars per story.

Two dollars every time you risk your life, because in Poza Rica, where this story takes place, the years 2010-2016 were hell. The journalist who tells this story asks to leave out any detail that could reveal their identity, because the same people are still in power and the risk still exists a decade later.

«If something happened to you before and you went to the police, they would hand you over to «them.»

You couldn’t even go out at night or be in dark places. It was terrible.There were thousands of crimes here that weren’t made public.They weren’t in the press or anywhere else because they didn’t want them to be public (…).»

When they got rid of the police, everything got better. (…) Now there are four [cartels]: Zetas calling themselves Grupo Sombra, the Sinaloa cartel, Jalisco [New Generation], and the old-school Zetas.In the main square of Poza Rica, the murals from the oil boom era or the great work by Pablo O’Higgings depicting the golden years are barely visible.More and more banners of the disappeared are hung in the pavilion, from tree to tree, and on the footbridges.

At the other end of the state, in the southern region, is the basin of the Papaloapan River. In Tierra Blanca, one of the most important cities, it is said that the idea of free journalism has been completely eradicated.

«They had control over what you could write and what you could not write.

They would say, ‘You can write this, you can’t write that. Or you’d get to a news story, run into them, and they’d just gesture with their finger, ‘No.’

We wouldn’t even take our equipment out. They didn’t give us money or offer us money. They call us accomplices, but it’s not like that.» «Tierra Blanca was a ghost town for a while. We lived with our necks on the line,» recalls another journalist who also requested anonymity for security reasons. He continues to work and says that sometimes Tierra Blanca is still a ghost town. It used to be so because of kidnappings; now it is because of extortion, executions and shootings.

Similar accounts are repeated in different regions of the state of Veracruz, a territory so vast that it could be a country: 71,820 square kilometers. Lands ravaged by violence and fear, places where the police were (and sometimes still are) complicit in crime. So much so that the former governor, Javier Duarte, decided to disband the intermunicipal police forces. In Xalapa, in May 2011; in Veracruz-Boca del Río, in December; in Coatzacoalcos-Minatitlán, in May 2013; and two months later, in Poza Rica-Tihuatlán-Coatzintla.

Duarte disbanded all municipal police forces. The Navy took control of security, and armed forces were deployed throughout the state. On April 10, 2011, Duarte, along with former President Felipe Calderón, launched Operation Safe Veracruz, which paved the way for a single federal command with military troops, increased security resources, and the purging of police forces.

In theory, at least, because Duarte’s security chief, Arturo Bermúdez Zurita, had other plans.

«Captain Storm,» as he was known, was the secretary of public security and in charge of the state police, and he decided to create his own special forces. In 2012, Bermúdez deployed an elite unit called the Grupo Tajín, named after the region’s most important pyramid. At an event that Duarte did not attend, Bermúdez Zurita said that 206 police officers had been trained by the navy for four months. He affirmed that the goal was to «ensure first contact, rescue and action with the civilian population,» but the project barely lasted and hardly fulfilled these goals. Grupo Tajín was a corrupt force that sank a year later when elite officers kidnapped eight police officers in the municipality of Úrsulo Galván.The policemen are still disappeared.

In 2014, Bermúdez Zurita tried again with a second group, the Fuerza Civil. Once again, the promise of an elite group and the bet multiplied by ten: there were two thousand policemen. The former National Security Commissioner, Monte Alejandro Rubido, was present. But security did not improve with the Fuerza Civil, and the murky events multiplied.

Even before the end of the 2010-2016 government, journalist Noé Zavaleta published his book «El infierno de Javier Duarte» (The Inferno of Javier Duarte) (Proceso, 2016). By that time, he says, at least 470 municipal and state police officers had been arrested «to be investigated for federal crimes, especially those related to drug trafficking.» His research shows that both Los Zetas and the Jalisco New Generation Cartel had «infiltrated the police forces» and even divided territory, with police from the mountains and southern regions working with Los Zetas and those from the coast and Sotavento working with the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG).

Another writer, Juan Eduardo Mateos Flores, describes the metamorphosis of the police in the port of Veracruz in his book «Reguero de Cadáveres» («Trail of Bodies»). He recounts how this area, which was completely under the power of Los Zetas, whom they called «La compañía» («The Company»), began to mutate under the control of «Zetas volteados» («Turned Zetas»).

Wearing thick-rimmed glasses, flip-flops, and speaking in slang, Mateos Flores recounts the change in territorial control through the stories of young people who died in the neighborhoods. He recounts the exact moment the new cartel entered the zone: «They threw 35 bodies in the street and introduced themselves as matazetas. Since then, however, these people had begun to work for the New Generation Cartel of Jalisco without knowing it.”

Noé Zavaleta, the young journalist who dared to cover Veracruz for Proceso after the murder of Regina Martínez, highlights two names that are always present in the darkest stories of the Veracruz police at that time: Arturo Bermúdez Zurita, «the ominous Captain Tormenta,» and, among his most powerful subordinates, Marcos Conde, head of the Security Secretariat in the Sotavento region.

It is no secret in Veracruz that Bermúdez Zurita’s police force was part of and involved with organized crime in several regions. But Zavaleta, tall and smiling, with an unusual frankness in this territory where everything seems silent, announced that at least three training camps had been discovered where state police officers were training young Zetas hitmen (sicarios). In Cumbres de Maltrata and Rancho San Pedro, for example, they were taught to shoot, but also «to dig clandestine graves without leaving traces, to torture and to kill.

Masters of crime.

Violence in Veracruz did not come out of nowhere with the Duarte administration. It had been growing for several years, and many identify the beginning of the worst times in 2007, when the dominance of Los Zetas began. This was during the time of Fidel Herrera. This former governor was nicknamed Zeta 1.

The violence continued through the Herrera and Duarte administrations; the Veracruz-born writer Fernanda Melchor, in the prologue to «Reguero de Cadáveres,» refers to this period as «the double six-year term.» Noé Zavaleta describes Duarte’s era as «true obscurantism.» He does not choose his words lightly, speaking of the effects of the cartel disputes, the redistribution of territories, and the multiple strategies the government pursued against the press.

– Duarte was a close friend of the media owners. For example, he invited the executive director of Diario de Xalapa to foreign destinations at least three or four times. In 2013, during the tourism fair in Madrid, Duarte took 15 of them on a trip. He even invited them to the Copa del Rey final at the Santiago Bernabeu stadium.

These media owners travelled around, received millions of pesos in contracts, but paid their journalists miserable wages. Horacio Zamora never went on those trips. He was a journalist for 15 years at various media outlets in Xalapa and the port of Veracruz, working directly with some of them and selling content to others. These were times of executions, bodies in bags, and disappearances while he tried to make a living as a freelance journalist. He covered those years under that kind of violence, but a decade later he realized that there were other kinds of violence besides the bloodshed in the streets.

– At that moment, you don’t realize it; you’re used to thinking that it’s just the boss, or the politics of the paper, or that it’s just the profession of journalism. But the truth is that they have violated so many of your rights – labor, civil, and professional. Now you see it and you realize that you were being exploited and abused, and they were doing whatever they wanted. I have witnessed countless cases of abuse. The infamous censorship of freedom of expression and freedom of the press starts in the newsrooms with miserable salaries, working 12-15 hours. You have no medical benefits; if something happens to you, you are on your own. You work with your own car and your own resources. I think I had maybe 9 or 10 jobs at the same time in Veracruz.

He is able to see this from a different perspective because time has passed, but also because he is no longer here. He left. For the second time, he went into exile in a safer country.

– I think everyone wants to flee Mexico, don’t they?

Sergio Landa was a writer and photographer at Diario Cardel. He earned 5,000 pesos a month without medical benefits or days off.

Rubén Espinosa Becerril earned the same as a photographer in Xalapa, while Gabriel Huge earned a little more, 3,000 pesos a week, in the port area.

Gregorio Jiménez worked in the municipality of Villa Allende as a writer and photographer, earning 20 pesos per article. On busy days, he sometimes earned 100 pesos, or about 1,700 pesos a month, plus 800 pesos for gas when he worked for the Liberal del Sur, a newspaper owned by the family of judge Edel Humberto Álvarez Peña, who has been accused of ghost contracts worth millions.

Similarly, in Coatzacoalcos, a qualified staff journalist at Notisur earned 3,600 pesos per month, while interns and students earned between 1,400 and 2,000 pesos per month.

The situation was similar in the port area. Journalists earned between 5,000 and 6,000 pesos per month at most companies. Only the most popular newspaper, Notiver, paid around 17,000 pesos per month.

In dollars, these numbers are painful: salaries of $500 per month for qualified journalists; half (or less) for those without formal training, the self-taught, the «empirical.» Full days of work for a salary of 8 to 16 dollars.

Hich owns

– «Sometimes it’s impossible to get out of this situation,» says one journalist. «If you ask me, did you have a relationship with these people [drug traffickers]? I can tell you that you have to learn to coexist with many of them, otherwise you won’t survive».

– The Zetas paid 15 to 20 thousand pesos a month to the media that collaborated with them, says another journalist from the port.

– Up to four times what a newspaper pays. How do you say «no» when the needs are greater? How to say «no» when there is no room to decide? How do you say «no» when it could get you killed today?

They did not always pay, not everyone got paid. But everyone was asked to do what they said.

– Nothing was optional. It wasn’t optional for those dedicated to police reporting to accept or reject the editorial line of the criminal group (…) I have heard testimonies of people who, when they diplomatically refused to follow the criminal group’s line, to go along with it, as they say in colloquial language, well, they faced consequences (…) They were deprived of liberty, tortured» – says Jorge Morales, former member of the Commission for the Attention to Journalists.

– Either you are with them or you are with them, said a policeman to Sergio Landa, who was kidnapped for the first time hours later.

On one side were bosses who demanded much and paid little; on the other, armed people who were above the law. For many, it was impossible to refuse: either you obeyed orders or your life was over.

4. The press as booty.

Just three families controlled at least 24 media outlets in Veracruz, and many of the owners of news companies were also politicians who held public management positions.

Edel Álvarez Peña, associated with the Olmeca Editorial Group, owned eight media outlets in Veracruz during Duarte’s term (plus four more in Chiapas and Tabasco). He had no background in journalism. During his decades-long political career, he served as mayor of Coatzacoalcos, state president of the PRI, advisor to the state government coordinator, and director of the Public Property Registry, among other positions. He was proposed as a judge by then Governor Fidel Herrera and appointed by the State Congress in 2010. Later, in December 2016, on the first day of the administration of Miguel Ángel Yunes Linares, he was appointed president of the Supreme Court of Justice and the State Judicial Council. He recently retired and was accused of corruption, including forging contracts worth around 350 million pesos with ghost companies linked to the international money laundering scandal known as the Panama Papers, according to the journalistic investigation by Flavia Morales.

The second media conglomerate in Veracruz with a clear conflict of interest is the La Voz del Istmo and Imagen del Golfo group, which owns five newspapers owned by the Robles-Barajas family. All of them are headed by José Pablo Robles Martínez, husband of Roselia Barajas y Olea, who was a federal deputy (1997-2000) and continued his political career by becoming ambassador to Costa Rica, appointed by the government of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador. Their daughter, Mónica Robles Barajas, has been a deputy twice (2013-2016 and 2018-2021), first for the Green Party and later for Morena. She was a deputy and at the same time the legal representative of the editorial group, according to the media registry of the Secretariat of the Interior. Mónica Robles’ husband, Iván Hillman Chapoy, is a former mayor of Coatzacoalcos, and her brother, Pablo Robles Barajas, has been a senior official at the National Water Commission since 2012. The companies owned by the Robles-Barajas family have received so many official advertising contracts that former governor Fidel Herrera criticized Pablo Robles Martínez in the past, calling him a «professional vacuum cleaner.»

Third, but not least, is Grupo Editorial Sánchez, owned by the Sánchez Macías family. They have been in the news business for decades, but Duarte’s sexenio was their heyday: they had up to 11 newspapers and a magazine, of which only seven survived. Unmistakably, they are all called El Heraldo. They had editions in Xalapa, Veracruz, Tuxpan, Poza Rica, Martínez de la Torre, Coatzacoalcos and Córdoba. The Córdoba branch was created during the Duarte administration. According to media reports from the day of the opening, March 21, 2014, state and federal officials were present. The ribbon was cut by Antonio «Tony» Macías Yazegey, father of Karime, father-in-law of the governor at the time, along with Eduardo Sánchez Macías, the man who publicly leads the group.

The governor’s wife and the owner of the media conglomerate share the same surname. They are said to be cousins or distant cousins. Without showing any birth certificates, Eduardo Sánchez Macías denied it when the Duarte government wavered. Beyond this possible kinship, Sánchez Macías was also a local deputy while he was in charge of these newspapers. In 2019, he ended up in jail for the crime of «simulation fraud» for allocating advertising from Congress to his own newspapers.

Former governor Miguel Ángel Yunes said that between 2010 and 2016, Duarte’s government awarded contracts worth 230 million pesos (more than $11 million) to his relatives. The case of Grupo Editorial Sánchez has not yet been resolved. Whether or not Eduardo Sánchez Macías was related to the governor, there is still a conflict of interest. At the same time as being a legislator, he was a media entrepreneur and, on top of that, he was appointed secretary of the State Commission for the Attention and Protection of Journalists.

Eduardo Sánchez Macías’ political career has included membership in several political parties: he went through the ranks of the PRI, then became a member of the Mexican Green Party, then Nueva Alianza, later Movimiento Ciudadano, and is currently a member of Morena.

Another politician and media entrepreneur is José Alejandro Montano Guzmán, head of Milenio El Portal, a newspaper that also mysteriously disappeared with the end of Duarte’s term. Montano Guzmán belongs to a family linked for several generations to the security forces of the PRI governors of Veracruz. He was a military officer and secretary of security during the six-year administration of Miguel Alemán Velasco (1998-2004). He later studied public administration and law before fully entering the political world. Montano was a local deputy for the PRI (2004-2007) and a federal deputy (2012-2015), while directing the Veracruz branch of the newspaper Milenio. Gina Domínguez Colio, the strong woman of the Duarte government who distributed the large advertising contracts, previously worked as the editor-in-chief of this newspaper, and the editor was none other than the journalist Víctor Báez Chino, who was later assassinated.

These are just a few examples that illustrate the blurred line between public and private in the media landscape of Veracruz at that time: government officials ran editorial offices, others owned communication industries, and some politicians were shareholders or founders of newspapers. These connections conditioned editorial lines and created dubious editorial commitments.

«My boss called me one day, very upset,» says a journalist from Xalapa. – «Hey, I heard you were involved in this, right? Don’t you realize you’re hurting me? I have a deal here that could fall through if you keep this up. He told me to back off. «You’d better, otherwise I’ve been told they’re going to mess you up. I’m telling you, I have direct contact with the state government.»

He recounts a time when he participated in a protest in Congress and the police beat him in front of the deputies, and how one of them, sitting on a bench, witnessed the abuse without saying anything. The same deputy held a leading position in the media company where he worked.

To understand the multimillion-dollar official propaganda contracts of the Duarte government with media companies, it is necessary to mention the Capital Media Group, owned by the Maccise family, founded in the 1980s by Anuar Maccise Dibb and inherited by his sons José Anuar and Luis Ernesto Maccise Uribe. They had 13 media outlets throughout the country, including television (Efekto TV), radio (Capital), and various specialized print publications such as The News and Estadio, although they had only one newspaper in Veracruz: Capital Veracruz.

There are documents showing that the government owed them nearly 8 million pesos, which was allocated to their newspaper, Reporte Índigo. But they didn’t just receive advertising: in two direct awards in 2014 and 2015, the Veracruz government spent 66 million on granola bars, 47 million on amaranth bars, and other NutriWell brand products from the Maccise Uribe brothers, for a total of 191 million and 315 thousand pesos. According to Sebastián Barragán’s journalistic research, this purchase was for the supplies that would be delivered for school breakfasts in public school cafeterias.

The Maccise Uribe brothers, friends of former President Enrique Peña Nieto, received similar contracts for school lunches in the state of Mexico and are linked to possible embezzlement of up to one billion pesos. In addition, according to journalist Omar Fierro, both Peña Nieto and Emilio Lozoya Austin, former director of Petróleos Mexicanos, and other former high-ranking officials currently under investigation for various acts of corruption, listed their addresses at Montes Urales 425, the headquarters of Grupo Mac Multimedia and the Maccise Uribe law firm. And there is another interesting detail: José Antonio García Herrera, a lawyer for Mac Multimedia, is listed as the editor of the Capital Group newspapers.

Media entrepreneurs were also government officials, and vice versa: the press was an endless revolving door for millionaire deals in Mexican politics.

People with power used information as a way to steal money, blackmail other politicians, and advance (or destroy) careers. Economic rather than editorial projects. The press was used as a tool or channel for corruption. And in the middle of it all, journalists were trapped with meager salaries and many risks. At least four of the victims worked in the companies of the aforementioned politicians: Gregorio Jiménez, Sergio Landa and Gabriel Fonseca at Grupo Editorial Olmeca, and Víctor Báez Chino at Milenio El Portal.

5. The call.

The phone kept ringing, but Gabriel Huge did not answer it, even though it was right next to him. He looked worried. Mercedes, his aunt who raised him as her own son, looked at him.

«Why don’t you answer?»

«They’re calling me, but don’t worry, I’ll change the number.»

He did. By May 2, 2015, he already had a new phone number, but they found him anyway. He left, saying he would be right back, but he never returned.

Eventually, his family was able to reconstruct some of the events. That morning, Huge went downtown to cover a press conference, a routine procedure for police reporters. His colleagues say he was calm; they noticed nothing out of the ordinary. Around eleven, he returned home with his family, where Mercedes and Isabel chatted with him briefly. His nephew, a fellow photographer, asked if he had «been there.» Huge replied, «I’m just leaving,» and left without his motorcycle. They never knew where, but someone later told them that he had been to a place called El Cristo. Antonio Rebolledo, a friend, told the family that Huge had stopped by his shop that afternoon, explained that he was on his way to a sensitive meeting, and asked him not to call or make a fuss. He added, «If I’m not back in two hours, take good care of my daughter.

The next morning, with no news, the family began to worry. Huge did not answer his phone, and he had not returned. The authorities announced the discovery of four bodies, two of them the uncle and the nephew.

Mutilated. In garbage bags and thrown into a canal called La Zamorana.

It was May 3, 2015, Freedom of Expression Day.

People smile when Gabriel Huge is mentioned; nostalgia wells up, followed by sadness, perhaps for his untimely death or for the way he was killed. «Uge» is pronounced as it sounds in Spanish, with a silent «h». He was well known among journalists who covered police news. They called him «the mariachi» because in his early days as a photographer, he carried a Pentax SLR camera in a violin case, the only thing he could find to protect it from the bumps and bruises of chasing stories, accidents or deaths around the clock.

– «100% police reporter,» recalls Horacio Zamora, also a photographer. He was in the thick of it, the first to arrive, but also the one who shared his photo with those who couldn’t make it in time. He gave advice and everyone listened. He was a leader.

Mariachi, a 37-year-old photojournalist, covered crime stories for more than a decade. His pictures appeared every day in «Sucesos,» the most viewed section of Notiver, the most popular newspaper in Veracruz at the time.

When Huge’s colleague and friend Milo Vela was killed, along with his son Misael López and his son’s mother, Agustina Solana, he was deeply affected, as were many journalists in the port city of Veracruz. A month later, when another colleague, Yolanda Ordaz of Notiver, became the third journalist from the same newspaper to be killed, Huge decided to flee. He was part of an exodus of displaced reporters-those who sought refuge as best they could or left journalism to work on something else. An almost invisible, poorly documented exodus from a time some call «the retreat.»

Huge went first to Tabasco and later to Poza Rica, where colleagues remember him fondly for the sympathy he garnered, even if his stay there was brief.

«He gave me a photo gallery and left me his Nextel phone with all his contacts; he seemed very concerned,» says Lydia López, a journalist and teacher in the northern region of Veracruz.

He had never worked as a radio broadcaster, but he did in Poza Rica. He was the enterprising type, not afraid to try new things. In addition to reporting, he spent time in pawn shops looking for bargains. He bought several computers and decided to open a cybercafé, recalls Isabel Luna, his niece, even though they were like brother and sister.

«Well, I’m not sure if the cybercafe came first, because he also opened a video store, we rented movies. Then he started buying tires, he wanted to open a tire repair shop. That’s how he was. That’s how many journalists were, then and now, who had no choice but to work several jobs to make a living. Like Pedro Tamayo Rosas, who had a food stand, or Sergio Landa, a former soccer referee, or Juan Atalo Mendoza Delgado, who drove a taxi».

After the murders of the Notiver journalists, there was an implicit ban on hiring anyone who had worked for that outlet in the port area. The media would not hire them, claiming that they were afraid of reprisals. Isabel remembers that her uncle had a project to start a newspaper, and it was well under way; he had even chosen a name: El Regional de Veracruz. It was a joint project with his nephew, Guillermo, and Ana Irasema Becerra, who sold advertising for the newspaper. The three of them, along with another photographer, Esteban Rodríguez, were found murdered on the morning of May 3.

– Why were they killed?

– We don’t know. We still don’t know. Sitting under a guava tree in the courtyard of their home in the Icazo neighborhood, where they have held conversations and parties for decades, Isabel and Mercedes respond with their eyes downcast. The same patio where they mourned Gabriel Huge and Guillermo.

Duarte came here to tell us that there would be an investigation, but nothing happened. Duarte just came to take a picture with us.

While the family mourned, the authorities tried to deal with one scandal after another. A week earlier, Regina Martínez had been murdered, and a few months before that, three other journalists from Notiver (Milo Vela, Misael López, and Yolanda Ordaz) had been killed. In Acayucan, Gabriel Fonseca, another journalist, had also disappeared, although no one spoke about him.

At the same time, the former federal prosecutor for crimes against freedom of expression, Laura Borbolla, arrived at the port of Veracruz to open the preliminary investigation AP/35/FEADLE/2012. There were condolences, flowers, and statements full of promises for justice. The government offered the family protection, even moving them out of the state for their safety. In white vans escorted by police cars, Mercedes, Isabel, and their children were taken to the state of Puebla.

They were kept there for only a week before being returned to their home.

Guillermo, known to everyone as Memo, was a serious child and adult. Isabel, his older sister, says that as a child he did not play much, only running around the yard. He had a sense of responsibility, and she believes that he might have liked to study, but he chose to work because he felt compelled to help support the household after their mother, Mercedes, was widowed. Later, when Isabel divorced, it was Huge and Guillermo who took care of buying diapers, milk, and everything else their nephews and nieces needed.

Memo completed his basic education, opting for technical training in air conditioning repair, but as soon as he finished his classes, he started working as a journalist. Always close to his uncle Gabriel Huge, who was already an experienced crime photographer and undoubtedly his role model in everything. After picking up the pace of reporting, Memo soon felt his calling as a police reporter. He was only able to work for two years, but they were very intense.

Makanaki has photos of Guillermo on his phone. He is seen standing guard at the scene of a car accident. Another is outside the prison, at the «base,» as crime reporters call the place where they wait for news.

Memo was wild; he loved to have a good time. He paid little attention to his work because he was always fooling around with the people around him. Memo was about six feet tall. Although he was a bit of a mess, he was very dedicated to his work. When it was time to work, he gave it all his energy and attention. I can attest to that because a couple of times I said to him, «Hey, Memo, are you going to the accident scene? Yes,» [he replied]. – Don’t be mean; cover for me; I don’t feel like going all the way out there. – Okay, I’ll give you some pictures» [he replied]. And off he went to take some really good pictures. I can’t say that Memo, Mariachi or Esteban Rodríguez were lazy. Maybe they were cheerful and wild, but I can’t say anything bad about them. They were always good to us and the rest of the group.

Makanaki is a well-known photographer in the port city of Veracruz. He is in his sixties now, but still rides around on his motorcycle, wearing a press vest and hanging camera. It saddens him to remember Guillermo as such a happy person and to think that he was killed at such a young age.

– He was so young. He was so young. He could have enjoyed more time as a crime reporter.

Guillermo was 21 years old.

His Facebook profile is still active, with frequent messages. His sister Isabel, his girlfriend Tania, and his friends continue to write on his wall. People congratulate him on his birthday and tell him they love and miss him.

In the photos he posted on Facebook, he looks happy, wearing sunglasses, in selfies, and with friends. Isabel says he liked reggaeton and salsa dancing.

– We rarely went to parties together. We went to a cousin’s quinceañera once; we were there when he got off work. I remember dancing with him; I think that only happened twice because we hardly ever danced together,» Isabel says.

They danced in the patio where the guava tree still stands.

In Veracruz, and perhaps in several states, members of the cartels call newsrooms to tell them what to publish and what not to publish. They call directors, journalists, and photographers; they call to give tips about something that has happened or is about to happen, suggestions that, more than being helpful, are instructions for mandatory coverage. In 2010-2016, there were cases in which these suggestions or tips on what to cover came so quickly that they led to absurd situations, such as journalists showing up before the bodies had even been dumped at the scene.

The narcos call because they have the phone numbers of journalists. When there is a new «plaza boss,» a new leader of the drug cartel in that area, one of the first things they do is get names, phone numbers, addresses, etc.

They call, but often do not even have to introduce themselves; everyone knows who they are. They are seen on the street, recognized and greeted. Often, especially in small towns, the new boss of the plaza used to be the municipal policeman or the traffic cop. He used to be your source, the one who gave you tips and whom you used to question until yesterday. And besides being a narco, he is a neighbor; he lives two or three houses down from you. Or you went to the same school; he is your childhood friend, your cousin’s husband, or even your compadre.

The phone rings; how can you not answer it? Is there a purpose to not answering?

This research shows that «pressure» or «collusion» are ambiguous words in Veracruz between 2010 and 2016: there was an inevitable, often forced, and always unequal relationship between the press and organized crime.

In May 2012, they called Gabriel Huge in Veracruz. He left without saying where he was going and never returned. They found parts of his body in garbage bags.

They called Noel López Olguín in Jáltipan, but he said he was on his way to Soteapan and would be back that afternoon. It was March 8, 2011. Three months later they found his body in an unmarked grave.

On January 22, 2012, they called Sergio Landa in Cardel. They called him every half hour and he turned pale. He rushed out and said: «I’ll be right back, don’t turn off the machine, I’ll be back to finish what I’m doing. According to people who have read the official investigation, security cameras recorded him arriving on his motorcycle at the Tamarindos gas station, where he met state police officers. Sergio followed the police car to a small restaurant on the Conejos-Huatusco highway. He left his motorcycle there and followed the police on foot toward Huatusco. No one has heard from him since.

They called Miguel Morales to the offices of Diario de Poza Rica on July 19, 2012. There was tension over a story he had reported the day before: a girl had drowned in the Cazones River. It was an accident, a local and normal piece of information, recalls a colleague from that city, who asked to remain anonymous. The night before, someone warned not to publish the information, and although the Diario de Poza Rica deleted it before sending the edition to print, it was published in another local media, Tribuna Papantleca, signed by Miguel Morales. His colleagues believe that this story was the reason for Miguel Morales’ disappearance. He had been a self-taught crime reporter for a short time. He was paid 40 pesos per story, so he published in several places. That Tuesday, July 19, he got the call, left his equipment at the newspaper’s front desk, and left. He did not return.

Four of them got the call. Maybe others did as well.

6.The crime reporters, the «empirical»

– What can you not talk about?

– Crime reporting.

Hugo Gallardo answers without hesitation. He is precise in his words, with the pauses and theatricality of an experienced television journalist, because he has 36 years of experience. For a long time, he was the face of Televisa in the port of Veracruz. He reported on crime, which became almost the only thing that area contributed to the national agenda: massacres, 35 bodies dumped in a roundabout, corpses and more corpses. These were times when the homicide rate in the state reached 23.5 victims per 100,000 inhabitants, which the World Health Organization considers akin to an epidemic of violence since 10 is the limit of what is considered normal.

Gallardo is tall, tanned, and has a perfectly trimmed mustache. His pants are pressed, and his shirt is so white it is blinding. He is preparing to start the noon news on his own radio station, which he started as a means of survival after the misfortune of being added to the list of those blacklisted by the print media.

Even in front of the cameras, he names politicians and cartels without euphemism; he has lost the fear of naming them. What cannot be talked about, he says, is the police source. Because the greatest risk is to be identified with that work. He knew this well when he was kidnapped after reading a short note on the air, just three lines, saying that bloodstains had been found in a car. Because of this routine broadcast on Televisa, he was kidnapped, beaten and tortured in a way so common in the port that it now has a name: «tablear.» Kidnapping. Beating. Torture. Humiliation, and then the aftermath, the stigma.

«In some places where I applied for jobs, they replied that there was an order from the governor not to hire me.»

The strategy was completed with another defamatory tactic: blacklists. New lists were said to exist all the time, and the names of journalists were circulated on social networks. Other times, there was just a list with no details, a rumor that many suspected came from government agencies.

Nobody trusts anybody anymore. Mistrust was sown. But more than that, the distrust was directed at crime journalists, because they were the ones who were killed – the perverse custom of being murdered and still being considered a suspect in your death. The prejudices of «they must have done something,» «they were involved in something,» echoed endlessly.

Being a crime journalist became a risk in itself. Of the 20 murdered and disappeared, 14 were dedicated to police information (only Regina Martínez did not cover it, and five others did so sporadically or focused on other topics): Noel López Olguín, Rubén Espinosa Becerril, Moisés Sánchez, Armando Saldaña, and Manuel Torres González). In addition, of the 20 disappeared and murdered, 17 were self-taught, «empirical».

Covering crime news is always risky. It involves dealing with dangerous sources, getting caught in the crossfire, and navigating crime scenes. But the danger for the press deepens when thousands of readers want to see the details of the dead, the faces of the victims, and the dripping blood. People like to see blood, say several journalists. In everyday work, this means the obligation to cover every violent event because the boss orders it, because all stories are needed to sell the newspaper. Those who do not cover these events lose their jobs.

More blood meant better newspaper sales and greater bargaining power for the news companies with the government. Because the media was successful and widely read, it was a good showcase for advertising, or because the authorities wanted to inhibit the publication of the violent present so that it was not known. Crime news became a crucial space where what was happening was shown, unfiltered. And it was a double-edged sword.

– People consumed a lot of blood (…) Newspaper vendors had meetings to let you know that you had to use the bloodiest photo, otherwise they wouldn’t sell the papers. Whoever had the bloodiest, most powerful photo was the one who actually sold (…) The newsstand vendors would tell you, «Can you report on the cartel’s dead guy? Because people want to know about that.» So there was a conflict between what the market demanded, so to speak, and what happened on an ethical level, and what the criminals wanted. Obviously, they did not want to show that they were at war and that they had lost on some occasions, so they would go directly to the newsrooms.

Sayda Chiñas is a journalist from Coatzacoalcos and one of the few people willing to speak openly in this region of water, oil, and fear. She was the supervisor and colleague of Gregorio (Goyo) Jiménez. Chiñas was also aware of the circumstances at the time, as she was a member of the State Commission for the Attention and Protection of Journalists (CEAPP).

Tall, strong-willed and outspoken, Sayda was the one who sprang into action when Goyo was kidnapped. She alerted colleagues in the capital to spread the news nationally and pressure for the reporter’s release. Authorities and media executives alike intimidated and threatened her, trying to keep her quiet. She resisted the pressure and continued to demand justice.

Years later, after the kidnapping and murder of her colleague Gregorio Jiménez, she sums up what she witnessed. How businessmen, executives and media owners viewed journalists:

The problem is that they see us as replaceable; there will always be a new journalist who will do the same job for less money. What they did was to cut the expenses of reporters. Also, sometimes municipal governments would pay for a report by a journalist. They would say, «I’m not paying for your work. You have to send me the piece, but the municipality will pay for it.» [We leave out the details of the named municipalities so as not to jeopardize her.]

Another twist in the power of agreements. But above all, several colleagues say that the media took advantage of the so-called «empirical» or reporters by trade to compete among the media and sell more. These were journalists who had not had the opportunity for formal training, but had gained experience only through field work. When the situation became dire, experienced journalists resisted, saying «I will not do that» or complaining that their writing was being changed. In response, bosses turned to people desperate for work, exploiting their lack of training and even their desire to stand out.

In exchange for meager wages – 20 to 40 pesos per article – they were sent to cover the most complex events, also exploiting their legitimate personal ambitions. Working as a police reporter was an attractive position: they became the most read and recognized people in their communities, the ones who told the truth about what was happening.

These were the cases of Gabriel Fonseca, a 17-year-old who reported on police affairs in Acayucan (2011), or Miguel Morales, who went from working as a cleaner to becoming a police reporter in Poza Rica (2012), or Sergio Landa, formerly a painter, sign maker, and soccer referee, who became a reporter in Cardel (2013), as well as Gregorio Jiménez, who reported on police affairs after being a social photographer and construction worker (2014).

The youngest or those most in need were sent to a front that was difficult to control, even for those with formal education. They were sent to the field by editors, directors and bosses who only thought about the cover that would sell the most, but without any guarantee, protection or support for the reporters.

Something similar is happening today in the battle for likes. Live broadcasts on Facebook and social media have become extremely popular and even massive, with thousands of people watching crime scenes live. And while it is profitable, as pages like «Veracruz on Alert» already have many advertisers, everything indicates that live streaming is the new crime news.

The police reporter is born out of necessity, but also for fun, nobody denies that.

Smiling like kids who have pulled a prank, some reporters say it is a kind of addiction. The thrill of outrunning ambulances at high speed, the joy of getting the best exclusive photo, and the competition to make the front page or take the picture that will go viral. Crime reporters admit they are brave and even cunning, but it is clear that the profession has become excessively dangerous – almost like receiving a death sentence. It happened without warning. Many did not realize what was happening. Of the twenty people who were killed and disappeared, only Regina Martínez had decided not to report anything that had to do with the police.

– They did not know where the beatings were coming from, as the cartoonist Rafael Pineda, known as Rapé, described. The worst panic attack was not knowing where the violence was coming from. He also fled the country and later moved to Mexico City to sleep more peacefully.

In a state embroiled in a struggle for control, in an area where cartels, police, politicians and businessmen were at odds, being a police journalist meant being caught in the crossfire. Gunshots came from the drug cartels, but also from vague enemies who were allies one day and switched sides the next. It was a blind shootout.

7. Forms of death

It was a little later than usual that night. It was past eleven, and Víctor Báez Chino was about to leave the newsroom. He was the director of Reporteros Policiacos, a portal created by journalists that in less than four years had managed to be sustainable and even grow. They started with a biweekly edition, then made it weekly because of reader demand and because they got sponsors for advertising, no longer depending on government contracts. Everyone in Xalapa read it. Colleagues from different regions called and asked to work for free.

It was an unusual but understandable success: the violence generated a lot of information, the public wanted to consume it, and several experienced journalists came together in the new portal. Víctor was the leader of the project. He had 25 years of experience working for different media, such as El Diario de Xalapa, AZ Diario, El Martinense, El Sol de Córdoba, and at that time he was also the editor of the police section of Milenio El Portal, the Veracruz branch of the national newspaper Milenio. In addition, Víctor was one of those people who gathered others around him, who called and organized others (just like Rubén Espinosa Becerril, another victim).

That night, Víctor was late leaving because an assistant, his niece, asked him to do a few things. There were still several workers in the offices. At 11:30 p.m., they all decided to leave; the workday of Monday, June 13, 2012, was considered over.

Once they were outside on Chapultepec Street, a gray van arrived. Armed men got out. Of the five people present, only Víctor Báez Chino was taken away.

Four hours later, around 4 a.m., they left his remains in the street. His mutilated body in a black garbage bag. In front of the IMSS offices and a few blocks from the Government Palace.

– Each situation of violence against journalists was unique, says Noé Zavaleta, who has worked as a reporter for more than ten years. He says this in an effort to avoid simplistic explanations, so as not to fall into a superficial analysis that looks for single culprits. He says this because he knows his state (Veracruz), was born in Xalapa, still lives there, and has worked there as a reporter for more than ten years. Zavaleta is right: only in Xalapa do you feel the weight of the political capital, surrounded by ears that observe in detail, or those that take note of everything and ask questions when you take out a camera. It is different in Veracruz-Boca del Río, the economic capital, where the territorial dispute over the conquest of a port that moves all kinds of goods is still perceived through gunshots and blood. The problems in Coatzacoalcos are different. This city has suffered an epidemic of kidnappings of oil workers, who earn good salaries. The zone has not been able to control extortion because it is said that no one, not even the largest petrochemical company, signs contracts without the approval of the zone’s head. The reign of terror and silence in Poza Rica is also different; it is a declining oil region, too close to Tamaulipas and the route to the United States, where few dare to speak.

There is no single explanation for the crimes against journalists in Veracruz, no single executioner, and no single method of killing. But there are some coincidences and patterns that, if not universal, are repeated in several cases.

For example, 12 of the 17 journalists murdered had previously disappeared for hours, days or months. And if we add the 3 who are still disappeared, it turns out that 15 of the 20 victims were disappeared. Disappearance has been a constant, either as a precursor to murder or as a continuing fate in the present.

We do not have details on the circumstances of the disappearances in all cases, but of those for which we have information, 9 were kidnapped in public places, 3 in their homes, and one at the entrance to the media house where he worked.

Gregorio Jiménez was kidnapped in the morning as he was preparing to take his children to school in Villa Allende, near Coatzacoalcos. Five men came to his house in a single van. They had long and short guns. They said, «This is the photographer. They pointed a gun at one of his daughters so that he would not resist.

A larger group of 9 or 12 people in 5 vehicles arrived at the home of Moisés Sánchez in El Tejar, Medellín. They were armed with long rifles. They asked for him. There was no room to resist; they took him by force in front of his family, who could do nothing. They also took his camera.

An armed commando took Anabel Flores from her home. They were men in uniforms «that looked like soldiers,» with long guns, helmets, vests, and balaclavas, her family recalled. It was two in the morning. She was already in bed, in her pajamas, taking care of her newborn baby, when they dragged her away.

Little is known about the details of the moment their lives were taken. But only 4 of the 17 cases occurred in homes.

Regina Martínez was killed in her home in Xalapa. It is not clear what items were taken or if any work materials were missing, especially since it is suspected that the crime scene was tampered with. The government quickly proposed the hypothesis of a crime of passion, which it has maintained to this day, although her colleagues say that the murder was clearly related to her journalistic work, and she herself had asked her family to keep their distance because she was investigating something important.

Three members of the Velasco-Solana family were attacked in their home in Veracruz. In different ways, with various weapons and in different rooms, they took the lives of Miguel Ángel, his wife Agustina Solana, and their youngest son, Misael López, 21 years old. Both Milo and Misael were journalists.

Photographer Rubén Espinosa was murdered in Mexico City in the home of activist Nadia Vera. Both had fled Veracruz due to threats, and both were tortured. Three other women who were in the apartment – Mile Virginia Martín, Yesenia Quiroz and Alejandra Negrete – were killed first and in different ways.

In all three cases, the evidence suggests that the attackers spent some time in the homes. They did not kill the journalists quickly or with a single shot. There were signs of torture with various objects. These were planned operations involving several people. The assailants also made phone calls to other people. In front of the house of Velasco-Solana, for example, there were several trucks. And in the Narvarte neighborhood, where Rubén and Nadia were killed, there were cars waiting.

Two other victims were executed in the street.

Manuel Torres González was killed on the morning of May 15, 2016, on the street of 2 de abril, in a wealthy and theoretically safe neighborhood, in front of a clinic and near the transit offices of Poza Rica. He was killed with a single shot to the head. «It was very precise and carried out by a skilled shooter,» said his colleagues.

One night in July 2016, Pedro Tamayo was shot more than ten times with a 9mm gun at the door of his home while tending to the hamburger and hot dog stand he had set up with his family. The police, who were supposedly guarding him, were only a few feet away but did nothing. The ambulance took a long time to arrive. Before he was taken to the hospital where he died, he told his wife, Alicia Blanco:

«Don’t let them take me to Social Security, honey. The state police will finish killing me there. Take care of my children, my grandchildren, and stop receiving state security.

8. To cause pain (and terror).

Blade wounds to body and head.

33 shots to 3 bodies with 9mm, .38 Super and .380 caliber weapons.

The body showed signs of torture and was decapitated.

One wound on the cheek, three holes apparently caused by a blackjack glove.

Legs detached and severed.

Beating on the body.

Gunshot to the head.

Semi-naked woman, tied up and her head covered with a plastic bag.

Bruises on the back.

12 stab wounds.

Various wounds and dismembered lower limbs.

Sitting man, with disfigured face.

Male. Upper and lower limbs bound with gray tape.

Had bruises on his body and fists tied behind his back.

Blindfolded with blows all over his body.

Male with burns and abrasions to the neck. Probably strangled first, then decapitated and mutilated.

Woman lying face down in a pool of blood.

Decapitated body with signs of torture and the head cut off.

The hands were tied behind the back. The body was held in a «sitting position».

He died from a blow to the head.

Asphyxia by suffocation.

Anoxia from strangulation.

Woman suffocated with a bath towel.

Hypovolemic shock caused by amputation and decapitation.

Man. Dismembered, tied at the chest and abdomen with a nylon rope.

Tongue cut off and dismembered. The tongue was not found.

The head was severed. The remains were left in bags in front of the offices of a media company.

Tortured and shot 4 times in the back of the head.

Male. Found in a clandestine grave inside a safe house.

One ear was cut off.

His arms were severed and his hands were cut off.

Skinned man. The skin has been removed from the face and part of the neck.

The bodies had been executed with a coup de grâce.

Found in a field.

Body found on the road.

Remains found in garbage bags on the street.

Half-naked man, tortured and blindfolded.

That’s what happened to the 17 journalists murdered in Veracruz between 2010 and 2016. It is not necessary to reveal their names or what torture, mutilation or dismemberment corresponds to each case; it is enough to know that this is what happened during the crimes committed. These are not invented words, but information scraped from files, excerpts from death certificates, and details leaked to the press. Words that speak of people, their bodies and their lives.

Two victims were suffocated, 6 were shot, 7 were decapitated and dismembered. Of the 17 murders, only 4 were instant deaths; of the others – 13 – we find that only in one case there is insufficient information, and in 12 others the victims showed signs of torture.

We still do not know what happened to Gabriel Fonseca, Miguel Morales and Sergio Landa, because they are still disappeared. Nor do we know what happened to Noel López Olguín, since his body was found three months after he was buried, without the possibility of a clear autopsy.

In addition, there are recurring elements in the third phase of the crime: disclosure. Of the 17 murdered journalists, only two were buried, or their bodies were deposited in unseen places. Fifteen were dumped in public places with the clear intention of being found. Sometimes in garbage bags, sometimes with cardboard signs or thrown on the ground. In downtown areas, in front of media outlets, on highways, and on the side of the road. Their bodies were almost always mutilated, thrown and displayed as messages of terror.

In Veracruz, journalists were not only murdered: they were first tortured, and then their mutilated bodies were exhibited. Methods convey messages.

First came control with agreements, calls, and instructions on what to publish and what not to publish. Then came the sowing of mistrust with blacklists and rumors about who was involved (with organized crime). Kidnapping, abduction, and beatings were ways to teach a lesson: «We are in charge here. Interrogation and torture were forms of intimidation, but also to obtain information because journalists «know things”.

Their methods of terror were torture, murder, and the display of bodies in pieces. This could be the manual of violence against the press in Veracruz from 2010 to 2016. At the national level, the media already have a kind of routine coverage when a journalist is killed: the name, the number on the list, and some details about their career, among other things.

From the outside, many of us may not have reported the details of the crimes, either because we did not know them or because we thought it was better not to, out of decency or ethical obligation. Inside Veracruz, however, the details of each murder and the actions taken against each victim are well known. These were warnings: «This could happen to you if we catch you.» This is the sound of silence.

In his book «Reguero de Cadáveres,» Juan Eduardo Flores Mateos recounts a scene that clearly illustrates the effect of these messages. It happened during those years at a meeting of journalists called by Pie de Página, in which some reporters from Veracruz participated. Daniela Pastrana, «who had connections with international organizations that help journalists in danger, asked Nacho [Ignacio Carvajal] what he needed to better cope with reporting in the port of Veracruz. «A gun,» Nacho said. «I need a gun.» Pastrana smiled nervously. In her friendly tone, she replied to Nacho, asking what good a small pistol would do against the weapons used by drug traffickers. «I want a gun so they don’t take me alive, Pastrana.» Silence fell over the table. Then Nacho continued. «Have you seen how these people torture, Pastrana? They’re primitive, rudimentary. They use hammers, screwdrivers. I want the gun in case I get caught; I’d rather shoot myself before they take me away.»

Javier Duarte is in prison, as is Marco Conde. Bermúdez Zurita, Gina Domínguez, and former state prosecutor Bravo Contreras were also imprisoned, but have since regained their freedom. And although almost ten years have passed since the end of that government, the situation in Veracruz remains very similar.

Journalists do not answer phone calls from unknown numbers. To contact them, you have to send them a message on WhatsApp, introduce yourself and ask someone they trust to recommend you. Only then do they agree to speak briefly, perhaps for an interview.

Many agreed to meet, only to cancel at the last minute. «I have nothing to contribute» was the most common explanation. Those who did speak were visibly affected; there were issues they simply could not address; they were crying or shaking with fear or anger. They requested anonymity for their safety, asking, «I will only speak off the record; do not even use my voice, or if you want to use it, it must be distorted.

Even when interviewed anonymously, most did not mention the names of former officials, businessmen, or drug cartels. They did not give last names or identities; they described or used other details to imply who they were referring to. If you finished the sentence with that name, they would just nod with a slight smile of satisfaction, indicating that you understood how things stood. If you said something absurd, they did not deny it; as if no one should know what they know.

Talking to journalists from this area is like constantly speaking in codes, as if the walls had eyes and ears. They live in a constant state of suspicion, as if they were at war.

The situation is also complicated for the families of the murdered and disappeared journalists. The terror is as present as in the first hours of the crimes. Some families agreed to be interviewed in order to write a biography, but seven families refused to participate at all.

They do not want to share information or even childhood memories. They are afraid that any details they give could put them at greater risk, and they know that if they are seen giving interviews, they will be exposed again. They are not exaggerating; in some places the killers are still active, have been promoted, or are now more powerful than before.

– «The one who ordered the disappearance of Cuco Fonseca is now a plaza boss.»

– We have been attacked by crime at the request of the government.

– We continue to walk in a mined world.»

These are the words of three journalists who asked that their names not be used.

Jorge Sánchez, Moisés Sánchez’s son, has been saying for the past few years that the former mayor of Medellín, who is suspected of killing his father, is walking around in public and getting away with it.

The relatives are also angry. They feel mistreated by the press, by colleagues, friends and neighbors. By those who spoke (and still speak) lightly of their loved ones.

For example, one of them said, «Because of our experience, we do not even want to name the situation. The unfair accusations and what people said hurt us a lot. And now that (the victim’s) son is starting to realize everything, we do not want him to go through what we went through.

The message arrives via WhatsApp. The sender is the aunt of one of the murdered journalists. She is kind and affectionate; she has been in dialogue for months, but she does not want to be involved in any public statements. Like her, several people explained their reasons for no longer participating in anything, in any exercise of remembrance, or even in any demand for justice. Others said no, thank you, or did not even respond.

Of the 33 people interviewed for this report, the majority requested anonymity.